Go Data Structures: Interfaces

Russ Cox

December 1, 2009

research.swtch.com/interfaces

Posted on Tuesday, December 1, 2009.

December 1, 2009

research.swtch.com/interfaces

Go's interfaces—static, checked at compile time, dynamic when asked for—are, for me, the most exciting part of Go from a language design point of view. If I could export one feature of Go into other languages, it would be interfaces.

This post is my take on the implementation of interface values in the

“gc” compilers: 6g, 8g, and 5g.

Over at Airs, Ian Lance Taylor has written

two

posts about

the implementation of interface values in gccgo.

The implementations are more alike than different:

the biggest difference is that this post has pictures.

Before looking at the implementation, let's get a sense of what it must support.

Usage

Go's interfaces let you use

duck typing like you would

in a purely dynamic language like Python but still have the

compiler catch obvious mistakes like passing an int where an object

with a Read method was expected, or

like calling the Read method with the wrong number of arguments.

To use interfaces, first define the interface type (say, ReadCloser):

type ReadCloser interface {

Read(b []byte) (n int, err os.Error)

Close()

}

and then define your new function as taking a ReadCloser.

For example, this function calls Read repeatedly to get all the

data that was requested and then calls Close:

func ReadAndClose(r ReadCloser, buf []byte) (n int, err os.Error) {

for len(buf) > 0 && err == nil {

var nr int

nr, err = r.Read(buf)

n += nr

buf = buf[nr:]

}

r.Close()

return

}

The code that calls ReadAndClose can pass

a value of any type as long as it has Read and Close methods

with the right signatures.

And, unlike in languages like Python, if you pass a value with the

wrong type, you get an error at compile time, not run time.

Interfaces aren't restricted to static checking, though. You can check dynamically whether a particular interface value has an additional method. For example:

type Stringer interface {

String() string

}

func ToString(any interface{}) string {

if v, ok := any.(Stringer); ok {

return v.String()

}

switch v := any.(type) {

case int:

return strconv.Itoa(v)

case float:

return strconv.Ftoa(v, 'g', -1)

}

return "???"

}

The value any has static type

interface{}, meaning no guarantee of any methods at all:

it could contain any type.

The “comma ok” assignment inside the if

statement asks whether it is possible to convert any to

an interface value of type Stringer, which has the

method String. If so, the body of that statement

calls the method to obtain a string to return.

Otherwise, the switch picks off a few basic types before

giving up.

This is basically a stripped down version of what the

fmt package does.

(The if could be replaced by adding

case Stringer: at the top of the switch,

but I used a separate statement to draw attention to the check.)

As a simple example, let's consider a 64-bit integer type

with a String method that prints the value

in binary and a trivial Get method:

type Binary uint64

func (i Binary) String() string {

return strconv.Uitob64(i.Get(), 2)

}

func (i Binary) Get() uint64 {

return uint64(i)

}

A value of type Binary can be passed

to ToString, which will format it using the String

method, even though the program never says that

Binary intends to implement Stringer.

There's no need: the runtime can see that Binary

has a String method, so it implements Stringer,

even if the author of Binary has never heard of

Stringer.

These examples show that even though all the implicit conversions are checked at compile time, explicit interface-to-interface conversions can inquire about method sets at run time. “Effective Go” has more details about and examples of how interface values can be used.

Interface Values

Languages with methods typically fall into one of two camps: prepare tables for all the method calls statically (as in C++ and Java), or do a method lookup at each call (as in Smalltalk and its many imitators, JavaScript and Python included) and add fancy caching to make that call efficient. Go sits halfway between the two: it has method tables but computes them at run time. I don't know whether Go is the first language to use this technique, but it's certainly not a common one. (I'd be interested to hear about earlier examples; leave a comment below.)

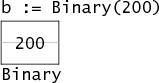

As a warmup, a value of type Binary is just a 64-bit integer

made up of two 32-bit words (like in the last post, we'll assume a 32-bit machine; this time memory

grows down instead of to the right):

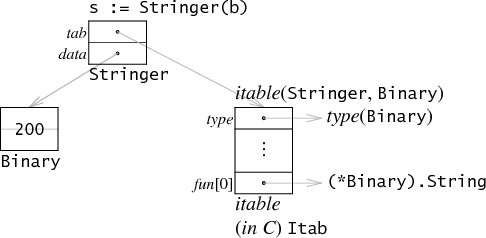

Interface values are represented as a two-word pair giving

a pointer to information about the type stored in the interface

and a pointer to the associated data.

Assigning b to an interface value of type Stringer

sets both words of the interface value.

(The pointers contained in the interface value are gray to emphasize that they are implicit, not directly exposed to Go programs.)

The first word in the interface value points at

what I call an interface table or itable (pronounced i-table; in the runtime sources,

the C implementation name is Itab).

The itable begins with some metadata about the types

involved and then becomes a list of function pointers.

Note that the itable corresponds to the interface type,

not the dynamic type. In terms of our example, the itable

for Stringer holding type Binary

lists the methods used to satisfy Stringer,

which is just String: Binary's

other methods (Get) make no appearance

in the itable.

The second word in the interface value points

at the actual data, in this case a copy of b.

The assignment var s Stringer = b makes

a copy of b rather than point at b

for the same reason that var c uint64 = b

makes a copy: if b later changes,

s and c are supposed

to have the original value, not the new one.

Values stored in interfaces might be arbitrarily large,

but only one word is dedicated to holding the value

in the interface structure, so the assignment allocates a

chunk of memory

on the heap and records the pointer in the one-word slot.

(There's an obvious optimization when the value does fit

in the slot; we'll get to that later.)

To check whether an interface value holds a

particular type, as in the type switch above,

the Go compiler generates code equivalent to the

C expression s.tab->type to obtain

the type pointer and check it against the desired type.

If the types match, the value can be copied by by

dereferencing s.data.

To call s.String(), the Go compiler generates

code that does the equivalent of the C expression

s.tab->fun[0](s.data): it calls the appropriate

function pointer from the itable, passing the interface value's

data word as the function's first (in this example, only) argument.

You can see this code if you run 8g -S x.go (details at the bottom of this post).

Note that the function in the itable is being passed the

32-bit pointer from the second word of the interface value, not the 64-bit

value it points at.

In general, the interface call site doesn't know the

meaning of this word nor how much data it points at.

Instead, the interface code arranges that the function

pointers in the itable expect the 32-bit representation

stored in the interface values.

Thus the function pointer in this example is (*Binary).String

not Binary.String.

The example we're considering is an interface with just one method. An interface with more methods would have more entries in the fun list at the bottom of the itable.

Computing the Itable

Now we know what the itables look like, but where

do they come from? Go's dynamic type conversions mean that

it isn't reasonable for the compiler or linker to precompute all

possible itables: there are too many (interface type, concrete type) pairs,

and most won't be needed.

Instead, the compiler generates a type description structure for each

concrete type like Binary or int or func(map[int]string).

Among other metadata, the type description structure contains a list

of the methods implemented by that type.

Similarly, the compiler generates a (different) type description structure

for each interface type like Stringer; it too contains a

method list.

The interface runtime computes the itable by looking for each method listed

in the interface type's method table in

the concrete type's method table.

The runtime caches the itable after generating it,

so that this correspondence need only be computed once.

In our simple example, the method table for

Stringer has one method, while the table for

Binary has two methods.

In general there might be ni methods

for the interface type and nt methods for the concrete type.

The obvious search to find the mapping from interface

methods to concrete methods would take O(ni × nt) time,

but we can do better.

By sorting the two method tables and walking them

simultaneously, we can build the mapping in O(ni + nt) time instead.

Memory Optimizations

The space used by the implementation described above can be optimized in two complementary ways.

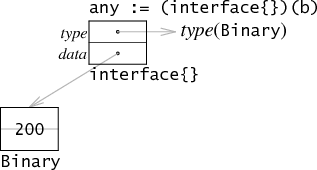

First, if the interface type involved is empty—it has no methods—then the itable serves no purpose except to hold the pointer to the original type. In this case, the itable can be dropped and the value can point at the type directly:

Whether an interface type has methods

is a static property—either the type in the source code says

interface{} or it says interace{ methods... }—so

the compiler knows which representation is in use at each point

in the program.

Second, if the value associated with the interface value

can fit in a single machine word, there's no need to introduce

the indirection or the heap allocation. If we define

Binary32 to be like Binary

but implemented as a uint32,

it could be stored in an interface value

by keeping the actual value in the second word:

Whether the actual value is being pointed at or

inlined depends on the size of the type. The compiler

arranges for the functions listed in the type's method table

(which get copied into the itables) to do the right thing with

the word that gets passed in. If the receiver type fits in a word,

it is used directly; if not, it is dereferenced.

The diagrams show this: in the Binary version

far above, the method in the itable is

(*Binary).String, while in the

Binary32 example, the method

in the itable is Binary32.String

not (*Binary32).String.

Of course, empty interfaces holding word-sized (or smaller) values can take advantage of both optimizations:

Method Lookup Performance

Smalltalk and the many dynamic systems that have followed it perform a method lookup every time a method gets called. For speed, many implementations use a simple one-entry cache at each call site, often in the instruction stream itself. In a multithreaded program, these caches must be managed carefully, since multiple threads could be at the same call site simultaneously. Even once the races have been avoided, the caches would end up being a source of memory contention.

Because Go has the hint of static typing to go along with the dynamic method lookups, it can move the lookups back from the call sites to the point when the value is stored in the interface. For example, consider this code snippet:

1 var any interface{} // initialized elsewhere

2 s := any.(Stringer) // dynamic conversion

3 for i := 0; i < 100; i++ {

4 fmt.Println(s.String())

5 }

In Go, the itable gets computed (or found in a cache)

during the assignment on line 2; the dispatch for the

s.String() call executed on line 4 is a

couple of memory fetches and a single indirect call

instruction.

In contrast, the implementation of this program in a dynamic language like Smalltalk (or JavaScript, or Python, or ...) would do the method lookup at line 4, which in a loop repeats needless work. The cache mentioned earlier makes this less expensive than it might be, but it's still more expensive than a single indirect call instruction.

Of course, this being a blog post, I don't have any numbers to back up this discussion, but it certainly seems like the lack of memory contention would be a big win in a heavily parallel program, as is being able to move the method lookup out of tight loops. Also, I'm talking about the general architecture, not the specifics o the implementation: the latter probably has a few constant factor optimizations still available.

More Information

The interface runtime support is in

$GOROOT/src/pkg/runtime/iface.c.

There's much more to say about interfaces (we haven't

even seen an example of a pointer receiver yet) and the

type descriptors (they power reflection in addition

to the interface runtime) but those will have to wait for future posts.

Code

Supporting code (x.go):

package main

import (

"fmt"

"strconv"

)

type Stringer interface {

String() string

}

type Binary uint64

func (i Binary) String() string {

return strconv.Uitob64(i.Get(), 2)

}

func (i Binary) Get() uint64 {

return uint64(i)

}

func main() {

b := Binary(200)

s := Stringer(b)

fmt.Println(s.String())

}

Selected output of 8g -S x.go:

0045 (x.go:25) LEAL s+-24(SP),BX 0046 (x.go:25) MOVL 4(BX),BP 0047 (x.go:25) MOVL BP,(SP) 0048 (x.go:25) MOVL (BX),BX 0049 (x.go:25) MOVL 20(BX),BX 0050 (x.go:25) CALL ,BX

The LEAL loads the address of s

into the register BX.

(The notation n(SP) describes the

word in memory at SP+n. 0(SP)

can be shortened to (SP).)

The next two MOVL instructions fetch the

value from the second word in the interface and store

it as the first function call argument, 0(SP).

The final two MOVL instructions fetch

the itable and then the function pointer from the itable,

in preparation for calling that function.

(Comments originally posted via Blogger.)

rog peppe (December 2, 2009 2:42 AM) Go's interfaces let you use duck typing like you would in a purely dynamic language like Python

this has been said a lot, but i don't think it's quite true. duck typing goes deeper. for instance, if i've got an API for doing arithmetic:

type Foo struct { ... };

func (f0 *Foo)Add(f1 *Foo) *Foo;

func (f0 *Foo)Negate() *Foo;

etc

with duck typing, this is compatible with any other type that responds to the same methods, including methods on objects that its methods return. if interfaces were really like duck typing, then the above struct would be compatible with this interface:

type Arith interface {

Add(f1 Arith) Arith;

Negate() Arith;

}

but it's not.

Fred Blasdel (December 2, 2009 3:26 AM) It's kind of worse than that rog: the Go language doesn't itself use the polymorphism mechanism it provides to its users (Interfaces), and the ones it does use (the parametricity of Array and Map) are for its use only.

They're understandably afraid of overloading, and classicist counter-revolutionaries could perturb the public development of the language (see Prototype.js for a particularly ironic and depressing example). They have to be careful about what they add.

I don't know whether Go is the first language to use this technique, but it's certainly not a common one.

I'm sure this is discussed in Cardelli and Abadi's "A Theory of Objects", but I don't have a copy of my own. I'd bet Rob has one you could borrow :)

Kalani (December 2, 2009 6:41 AM) Fred, I don't know why there should be any fear of overloading here (though you've put your finger on some major problems with this language). Especially with the poor String/toString example, somebody should have immediately seen a need to introduce overloading. Hopefully there's a better justification for accepting the unnecessary time/space overhead (and more importantly the logical/reasoning overhead) that goes along with runtime type-tag checking.

It's a shame -- the authors of Go should have read Mark Jones's dissertation on qualified types. Without polymorphic recursion, they could statically construct all necessary "interfaces" for primitive types and have a much nicer 'toString' function (not to mention a million other examples).

These guys missed a great chance to seriously advance the state of "system programming."

Evan Jones (December 10, 2009 4:31 PM) Re: Method lookup performance. It seems to me that the example shown for Method lookup performance is not quite "fair." The issue, I think, for Javascript and Python, is that the call to s.String() could call a different method on each loop iteration, if the code changes the type or the instance.

Go is a bit more static, and I don't think this is possible. If Python/Javascript forbid changing methods on an object, then the method lookup could be recognized by an optimizer as being constant, and hoisted out of the loop.

But I haven't thought about this too hard, so I could be wrong.

Tom (July 18, 2010 8:57 AM) I don't know whether Go is the first language to use this technique, but it's certainly not a common one.

Haskell TypeClasses are implemented using a similar technique - each type (or set of types) implementing a typeclass is associated with a method table (called a dictionary) that is passed to functions requiring values of said typeclass.

Squire (October 14, 2010 9:45 AM)

I don't know whether Go is the first language to use this technique, but it's certainly not a common one.

Emerald computed lookup tables dynamically; we called them "AbCon vectors", because they converted from the abstract type (aka interface), known at compile time, to the concrete type of the object (aka class), which was sometimes know only at runtime. We also cached the AbCons.

Emerald also did typechecking more or less as you have described it in Go, with interfaces being structural (programmers didn't have to claim that they implemented an interface, they just had to do it), checking being static when possible but otherwise dynamic, and allowing run-time type interrogation and checked run-time conversions. Emerald also had methods with multiple return values and "comma assignments".

Are you sure that you didn't peek?

Russ Cox (October 14, 2010 7:46 PM) @Squire:

Wow.

I'm about halfway through the 2007 retrospective paper about Emerald and my blog post pictures might as well have been lifted from Figure 3.

I'm sure we didn't peek, but I think it's interesting how similar the backgrounds of the team members are. In the case of Go, Rob brought the concurrency ideas via Hoare's CSP, Robert brought the object sensibilities of a Smalltalk programmer, and Ken brought the focus on C-quality performance that led to essentially the same data structures Emerald used 25 years ago. That characterization obviously oversimplifies, but you can see the same backgrounds coming together in the paper's description of the original Emerald team.

It's very cool to see not only that other people explored this space years ago but also that they arrived at essentially the same design. The fact that this design point has been discovered multiple times by independent groups makes it seem somehow more fundamental.

Thanks so much for pointing this out. Finding out about these kinds of connections is such a thrill.

Drew LeSueur (December 5, 2010 2:42 AM) Thanks so much for the tutorial. Your code at the end really helped me understand some Go basics

Anonymous (June 5, 2011 7:43 PM) "It's very cool " -- It's not cool at all; it indicates insufficient search of the literature, which one can see throughout the design of Go. Experienced language designers look at Go and just shake their heads. But it's Rob Pike and Ken Thompson! Yes, exactly -- a couple of clever strongly opinionated eccentrics, whose idiosyncratic ideas, not deep knowledge of language design, drive the design of Go. We can see the same thing in Perl and in Java -- idiosyncrasies in opposite directions. And then there's D, which is a trainwreck because its author treats it like a personal project. Google could have hired Walter Bright and turned D into the far better alternative to C++ that it had the potential to be in the beginning -- although they could have done better yet by hiring someone like Martin Odersky.

jam (July 31, 2011 7:33 AM) One trick I noticed was missing was:

stringer = s.String

for i ...

print stringer()

Namely being able to pull out the attribute lookup outside the loop. I use that a lot, especially for comprehensions.

For go, it could still be helpful to avoid the extra indirections. But go doesn't seem to allow for bound functions and using:

F = func() string { return s.String() }

Actually makes things a lot worse.

Consultoria RH (December 11, 2011 9:56 AM) Este blog é uma representação exata de competências. Eu gosto da sua recomendação. Um grande conceito que reflete os pensamentos do escritor. Consultoria RH