Hash-Based Bisect Debugging in Compilers and Runtimes

Russ Cox

July 18, 2024

research.swtch.com/bisect

Posted on Thursday, July 18, 2024.

PDF

July 18, 2024

research.swtch.com/bisect

Setting the Stage

Does this sound familar? You make a change to a library to optimize its performance or clean up technical debt or fix a bug, only to get a bug report: some very large, incomprehensibly opaque test is now failing. Or you add a new compiler optimization with a similar result. Now you have a major debugging job in an unfamiliar code base.

What if I told you that a magic wand exists

that can pinpoint the relevant line of code or call stack

in that unfamiliar code base?

It exists.

It is a real tool, and I’m going to show it to you.

This description might seem a bit over the top,

but every time I use this tool, it really does feel like magic.

Not just any magic either, but the best kind of magic:

delightful to watch even when you know exactly how it works.

Binary Search and Bisecting Data

Before we get to the new trick, let’s take a look at some

simpler, older tricks.

Every good magician starts with mastery of the basic techniques.

In our case, that technique is binary search.

Most presentations of binary search talk about

finding an item in a sorted list,

but there are far more interesting uses.

Here is an example I wrote long ago for Go’s sort.Search documentation:

func GuessingGame() {

var s string

fmt.Printf("Pick an integer from 0 to 100.\n")

answer := sort.Search(100, func(i int) bool {

fmt.Printf("Is your number <= %d? ", i)

fmt.Scanf("%s", &s)

return s != "" && s[0] == 'y'

})

fmt.Printf("Your number is %d.\n", answer)

}

If we run this code, it plays a guessing game with us:

% go run guess.go Pick an integer from 0 to 100. Is your number <= 50? y Is your number <= 25? n Is your number <= 38? y Is your number <= 32? y Is your number <= 29? n Is your number <= 31? n Your number is 32. %

The same guessing game can be applied to debugging. In his Programming Pearls column titled “Aha! Algorithms” in Communications of the ACM (September 1983), Jon Bentley called binary search “a solution that looks for problems.” Here’s one of his examples:

Roy Weil applied the technique [binary search] in cleaning a deck of about a thousand punched cards that contained a single bad card. Unfortunately the bad card wasn’t known by sight; it could only be identified by running some subset of the cards through a program and seeing a wildly erroneous answer—this process took several minutes. His predecessors at the task tried to solve it by running a few cards at a time through the program, and were making steady (but slow) progress toward a solution. How did Weil find the culprit in just ten runs of the program?

Obviously, Weil played the guessing game using binary search.

Is the bad card in the first 500? Yes. The first 250? No. And so on.

This is the earliest published description of debugging by binary search

that I have been able to find.

In this case, it was for debugging data.

Bisecting Version History

We can apply binary search to a program’s version history instead of data. Every time we notice a new bug in an old program, we play the guessing game “when did this program last work?”

- Did it work 50 days ago? Yes.

- Did it work 25 days ago? No.

- Did it work 38 days ago? Yes.

And so on, until we find that the program last worked correctly 32 days ago, meaning the bug was introduced 31 days ago.

Debugging through time with binary search is a very old trick,

independently discovered many times by many people.

For example, we could play the guessing game using

commands like

cvs checkout -D '31 days ago'

or Plan 9’s more musical

yesterday -n 31.

To some programmers, the techniques of using binary search

to debug data or debug through time seem

“so basic that there is no need to write them down.”

But writing a trick down is the first step to making sure everyone can do it:

magic tricks can be basic but not obvious.

In software, writing a trick down is also the first step to automating it and building good tools.

In the late-1990s, the idea of binary search over version history was written down at least twice. Brian Ness and Viet Ngo published “Regression containment through source change isolation” at COMPSAC ’97 (August 1997) describing a system built at Cray Research that they used to deliver much more frequent non-regressing compiler releases. Independently, Larry McVoy published a file “Documentation/BUG-HUNTING” in the Linux 1.3.73 release (March 1996). He captured how magical it feels that the trick works even if you have no particular expertise in the code being tested:

This is how to track down a bug if you know nothing about kernel hacking. It’s a brute force approach but it works pretty well.

You need:

- A reproducible bug - it has to happen predictably (sorry)

- All the kernel tar files from a revision that worked to the revision that doesn’t

You will then do:

- Rebuild a revision that you believe works, install, and verify that.

- Do a binary search over the kernels to figure out which one introduced the bug. I.e., suppose 1.3.28 didn’t have the bug, but you know that 1.3.69 does. Pick a kernel in the middle and build that, like 1.3.50. Build & test; if it works, pick the mid point between .50 and .69, else the mid point between .28 and .50.

- You’ll narrow it down to the kernel that introduced the bug. You can probably do better than this but it gets tricky.

. . .

My apologies to Linus and the other kernel hackers for describing this brute force approach, it’s hardly what a kernel hacker would do. However, it does work and it lets non-hackers help bug fix. And it is cool because Linux snapshots will let you do this - something that you can’t do with vender supplied releases.

Later, Larry McVoy created Bitkeeper,

which Linux used as its first source control system.

Bitkeeper provided a way to print the longest straight line

of changes through the directed acyclic graph of commits,

providing a more fine-grained timeline for binary search.

When Linus Torvalds created Git, he carried that idea forward

as git rev-list --bisect, which

enabled the same kind of manual binary search.

A few days after adding it, he explained how to use it on the Linux kernel mailing list:

Hmm.. Since you seem to be a git user, maybe you could try the git "bisect" thing to help narrow down exactly where this happened (and help test that thing too ;).

You can basically use git to find the half-way point between a set of "known good" points and a "known bad" point ("bisecting" the set of commits), and doing just a few of those should give us a much better view of where things started going wrong.

For example, since you know that 2.6.12-rc3 is good, and 2.6.12 is bad, you’d do

git-rev-list --bisect v2.6.12 ^v2.6.12-rc3

where the "v2.6.12 ^v2.6.12-rc3" thing basically means "everything in v2.6.12 but _not_ in v2.6.12-rc3" (that’s what the ^ marks), and the "--bisect" flag just asks git-rev-list to list the middle-most commit, rather than all the commits in between those kernel versions.

This response started a separate discussion

about making the process easier, which led eventually to the

git bisect tool that exists today.

Here’s an example. We tried updating to a newer version of Go

and found that a test fails.

We can use git bisect to pinpoint the specific commit that caused the failure:

% git bisect start master go1.21.0

Previous HEAD position was 3b8b550a35 doc: document run..

Switched to branch 'master'

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/master' by 5 commits.

Bisecting: a merge base must be tested

[2639a17f146cc7df0778298c6039156d7ca68202] doc: run rel...

% git bisect run sh -c '

git clean -df

cd src

./make.bash || exit 125

cd $HOME/src/rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry

go list || exit 0

go test -count=5

'

It takes some care to write a correct git bisect invocation,

but once you get it right, you can walk away while git bisect

works its magic.

In this case, the script we pass to git bisect run cleans out any stale files

and then builds the Go toolchain (./make.bash).

If that step fails, it exits with code 125,

a special inconclusive answer for git bisect:

something else is wrong with this commit and we can’t say

whether or not the bug we’re looking for is present.

Otherwise it changes into the directory of the failing test.

If go list fails, which happens if the bisect uses a version of Go that’s too old,

the script exits successfully, indicating that the bug is not present.

Otherwise the script runs go test and exits with the

status from that command. The -count=5 is there because

this is a flaky failure that does not always happen: running five times

is enough to make sure we observe the bug if it is present.

When we run this command, git bisect prints a lot of output,

along with the output of our test script,

to make sure we can see the progress:

% git bisect run ...

...

go: download go1.23 for darwin/arm64: toolchain not available

Bisecting: 1360 revisions left to test after this (roughly 10 steps)

[752379113b7c3e2170f790ec8b26d590defc71d1]

runtime/race: update race syso for PPC64LE

...

go: download go1.23 for darwin/arm64: toolchain not available

Bisecting: 680 revisions left to test after this (roughly 9 steps)

[ff8a2c0ad982ed96aeac42f0c825219752e5d2f6]

go/types: generate mono.go from types2 source

...

ok rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 10.142s

Bisecting: 340 revisions left to test after this (roughly 8 steps)

[97f1b76b4ba3072ab50d0d248fdce56e73b45baf]

runtime: optimize timers.cleanHead

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 22.136s

Bisecting: 169 revisions left to test after this (roughly 7 steps)

[80157f4cff014abb418004c0892f4fe48ee8db2e]

io: close PipeReader in test

...

ok rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 10.145s

Bisecting: 84 revisions left to test after this (roughly 6 steps)

[8f7df2256e271c8d8d170791c6cd90ba9cc69f5e]

internal/asan: match runtime.asan{read,write} len parameter type

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 20.148s

Bisecting: 42 revisions left to test after this (roughly 5 steps)

[c9ed561db438ba413ba8cfac0c292a615bda45a8]

debug/elf: avoid using binary.Read() in NewFile()

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 14.146s

Bisecting: 20 revisions left to test after this (roughly 4 steps)

[2965dc989530e1f52d80408503be24ad2582871b]

runtime: fix lost sleep causing TestZeroTimer flakes

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 18.152s

Bisecting: 10 revisions left to test after this (roughly 3 steps)

[b2e9221089f37400f309637b205f21af7dcb063b]

runtime: fix another lock ordering problem

...

ok rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 10.142s

Bisecting: 5 revisions left to test after this (roughly 3 steps)

[418e6d559e80e9d53e4a4c94656e8fb4bf72b343]

os,internal/godebugs: add missing IncNonDefault calls

...

ok rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 10.163s

Bisecting: 2 revisions left to test after this (roughly 2 steps)

[6133c1e4e202af2b2a6d4873d5a28ea3438e5554]

internal/trace/v2: support old trace format

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 22.164s

Bisecting: 0 revisions left to test after this (roughly 1 step)

[508bb17edd04479622fad263cd702deac1c49157]

time: garbage collect unstopped Tickers and Timers

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 16.159s

Bisecting: 0 revisions left to test after this (roughly 0 steps)

[74a0e3160d969fac27a65cd79a76214f6d1abbf5]

time: clean up benchmarks

...

ok rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 10.147s

508bb17edd04479622fad263cd702deac1c49157 is the first bad commit

commit 508bb17edd04479622fad263cd702deac1c49157

Author: Russ Cox <rsc@golang.org>

AuthorDate: Wed Feb 14 20:36:47 2024 -0500

Commit: Russ Cox <rsc@golang.org>

CommitDate: Wed Mar 13 21:36:04 2024 +0000

time: garbage collect unstopped Tickers and Timers

...

This CL adds an undocumented GODEBUG asynctimerchan=1

that will disable the change. The documentation happens in

the CL 568341.

...

bisect found first bad commit

%

This bug appears to be caused by my new

garbage-collection-friendly timer implementation that will be in Go 1.23.

Abracadabra!

A New Trick: Bisecting Program Locations

The culprit commit that git bisect identified is a significant change to the timer

implementation.

I anticipated that it might cause subtle test failures,

so I included a GODEBUG setting

to toggle between the old implementation and the new one.

Sure enough, toggling it makes the bug disappear:

% GODEBUG=asynctimerchan=1 go test -count=5 # old

PASS

ok rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 10.117s

% GODEBUG=asynctimerchan=0 go test -count=5 # new

--- FAIL: TestDo (4.00s)

...

--- FAIL: TestDo (6.00s)

...

--- FAIL: TestDo (4.00s)

...

FAIL rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry 18.133s

%

Knowing which commit caused a bug, along with minimal information about the failure, is often enough to help identify the mistake. But what if it’s not? What if the test is large and complicated and entirely code you’ve never seen before, and it fails in some inscrutable way that doesn’t seem to have anything to do with your change? When you work on compilers or low-level libraries, this happens quite often. For that, we have a new magic trick: bisecting program locations.

That is, we can run binary search on a different axis: over the program’s code, not its version history.

We’ve implemented this search in a new tool unimaginatively named bisect.

When applied to library function behavior like the timer change,

bisect can search over all stack traces leading to the new code,

enabling the new code for some stacks and disabling it for others.

By repeated execution, it can narrow the failure down to enabling

the code only for one specific stack:

% go install golang.org/x/tools/cmd/bisect@latest

% bisect -godebug asynctimerchan=1 go test -count=5

...

bisect: FOUND failing change set

--- change set #1 (disabling changes causes failure)

internal/godebug.(*Setting).Value()

/Users/rsc/go/src/internal/godebug/godebug.go:165

time.syncTimer()

/Users/rsc/go/src/time/sleep.go:25

time.NewTimer()

/Users/rsc/go/src/time/sleep.go:145

time.After()

/Users/rsc/go/src/time/sleep.go:203

rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry.Do()

/Users/rsc/src/rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry/retry.go:37

rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry.TestDo()

/Users/rsc/src/rsc.io/tmp/timertest/retry/retry_test.go:63

Here the bisect tool is reporting that disabling asynctimerchan=1

(that is, enabling the new implementation)

only for this one call stack suffices to provoke the test failure.

One of the hardest things about debugging is running a program

backward: there’s a data structure with a bad value,

or the control flow has zigged instead of zagged,

and it’s very difficult to understand how it could have gotten

into that state.

In contrast, this bisect tool is showing the stack at the moment

just before things go wrong:

the stack identifies the critical decision point that determines whether the

test passes or fails.

In contrast to puzzling backward,

it is usually easy to look forward

in the program execution to understand why this

specific decision would matter.

Also, in an enormous code base, the bisection has

identified the specific few lines where we should start debugging.

We can read the code responsible for that specific sequence of calls

and look into why the new timers would change the

code’s behavior.

When you are working on a compiler or runtime and cause

a test failure in an enormous, unfamiliar code base,

and then this bisect tool narrows down the cause to

a few specific lines of code, it is truly a magical experience.

The rest of this post explains the inner workings of

this bisect tool, which Keith Randall, David Chase, and I

developed and refined over the past decade of work on Go.

Other people and projects have realized the idea of

bisecting program locations too:

I am not claiming that we were the first to discover it.

However, I think we have developed the approach further

and systematized it more than others.

This post documents what we’ve

learned, so that others can build on our efforts rather than rediscover them.

Example: Bisecting Function Optimization

Let’s start with a simple example and work back up to stack traces. Suppose we are working on a compiler and know that a test program fails only when compiled with optimizations enabled. We could make a list of all the functions in the program and then try disabling optimization of functions one at a time until we find a minimal set of functions (probably just one) whose optimization triggers the bug. Unsurprisingly, we can speed up that process using binary search:

- Change the compiler to print a list of every function it considers for optimization.

- Change the compiler to accept a list of functions where optimization is allowed. Passing it an empty list (optimize no functions) should make the test pass, while passing the complete list (optimize all functions) should make the test fail.

- Use binary search to determine the shortest list prefix that can be passed to the compiler to make the test fail. The last function in that list prefix is one that must be optimized for the test to fail (but perhaps not the only one).

- Forcing that function to always be optimized, we can repeat the process to find any other functions that must also be optimized to provoke the bug.

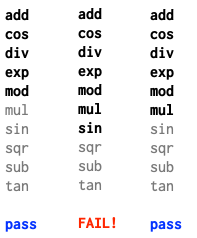

For example, suppose there are ten functions in the program and we run these three binary search trials:

When we optimize the first 5 functions, the test passes. 7? fail. 6? still pass.

This tells us that the seventh function, sin, is one function that must

be optimized to provoke the failure.

More precisely, with sin optimized, we know that

no functions later in the list need to be optimized,

but we don’t know whether any of functions earlier in the list must also be optimized.

To check the earlier locations, we can run another binary search

over the other remaining six list entries, always adding sin as well:

This time, optimizing the first two (plus the hard-wired sin) fails,

but optimizing the first one passes,

indicating that cos must also be optimized.

Then we have just one suspect location left: add.

A binary search over that one-entry list (plus the two hard-wired cos and sin)

shows that add can be left off the list without losing the failure.

Now we know the answer: one locally minimal set of functions to optimize to cause

the test failure is cos and sin.

By locally minimal, I mean that removing any function from the set

makes the test failure disappear: optimizing cos or sin by itself is not enough.

However, the set may still not be globally minimal:

perhaps optimizing only tan would cause a different failure (or not).

It might be tempting to run the search more like a traditional binary search, cutting the list being searched in half at each step. That is, after confirming that the program passes when optimizing the first half, we might consider discarding that half of the list and continuing the binary search on the other half. Applied to our example, that algorithm would run like this:

The first trial passing would suggest the incorrect optimization is in the second

half of the list, so we discard the first half.

But now cos is never optimized (it just got discarded),

so all future trials pass too,

leading to a contradiction: we lost track of the way to make the program fail.

The problem is that discarding part of the list is only justified if we know that part doesn’t matter.

That’s only true if the bug is caused by optimizing a single function,

which may be likely but is not guaranteed.

If the bug only manifests when optimizing multiple functions at once,

discarding half the list discards the failure.

That’s why the binary search must in general be over list prefix lengths, not list subsections.

Bisect-Reduce

The “repeated binary search” algorithm we just looked at does work, but the need for the repetition suggests that binary search may not be the right core algorithm. Here is a more direct algorithm, which I’ll call the “bisect-reduce” algorithm, since it is a bisection-based reduction.

For simplicity, let’s assume we have a global function buggy

that reports whether the bug is triggered when our change is

enabled at the given list of locations:

// buggy reports whether the bug is triggered // by enabling the change at the listed locations. func buggy(locations []string) bool

BisectReduce takes a single input list targets for which

buggy(targets) is true and returns a locally minimal subset x

for which buggy(x) remains true. It invokes a more generalized

helper bisect, which takes an additional argument: a forced

list of locations to keep enabled during the reduction.

// BisectReduce returns a locally minimal subset x of targets

// where buggy(x) is true, assuming that buggy(targets) is true.

func BisectReduce(targets []string) []string {

return bisect(targets, []string{})

}

// bisect returns a locally minimal subset x of targets

// where buggy(x+forced) is true, assuming that

// buggy(targets+forced) is true.

//

// Precondition: buggy(targets+forced) = true.

//

// Postcondition: buggy(result+forced) = true,

// and buggy(x+forced) = false for any x ⊂ result.

func bisect(targets []string, forced []string) []string {

if len(targets) == 0 || buggy(forced) {

// Targets are not needed at all.

return []string{}

}

if len(targets) == 1 {

// Reduced list to a single required entry.

return []string{targets[0]}

}

// Split targets in half and reduce each side separately.

m := len(targets)/2

left, right := targets[:m], targets[m:]

leftReduced := bisect(left, slices.Concat(right, forced))

rightReduced := bisect(right, slices.Concat(leftReduced, forced))

return slices.Concat(leftReduced, rightReduced)

}

Like any good divide-and-conquer algorithm, a few lines do quite a lot:

-

If the target list has been reduced to nothing, or if

buggy(forced)(without any targets) is true, then we can return an empty list. Otherwise we know something from targets is needed. -

If the target list is a single entry, that entry is what’s needed: we can return a single-element list.

-

Otherwise, the recursive case: split the target list in half and reduce each side separately. Note that it is important to force

leftReduced(notleft) while reducingright.

Applied to the function optimization example, BisectReduce would end up at a

call to

bisect([add cos div exp mod mul sin sqr sub tan], [])

which would split the targets list into

left = [add cos div exp mod] right = [mul sin sqr sub tan]

The recursive calls compute:

bisect([add cos div exp mod], [mul sin sqr sub tan]) = [cos] bisect([mul sin sqr sub tan], [cos]) = [sin]

Then the return puts the two halves together: [cos sin].

The version of BisectReduce we have been considering is the shortest

one I know; let’s call it the “short algorithm”.

A longer version handles the “easy” case of the bug being

contained in one half before the “hard” one of needing

parts of both halves.

Let’s call it the “easy/hard algorithm”:

// BisectReduce returns a locally minimal subset x of targets

// where buggy(x) is true, assuming that buggy(targets) is true.

func BisectReduce(targets []string) []string {

if len(targets) == 0 || buggy(nil) {

return nil

}

return bisect(targets, []string{})

}

// bisect returns a locally minimal subset x of targets

// where buggy(x+forced) is true, assuming that

// buggy(targets+forced) is true.

//

// Precondition: buggy(targets+forced) = true,

// and buggy(forced) = false.

//

// Postcondition: buggy(result+forced) = true,

// and buggy(x+forced) = false for any x ⊂ result.

// Also, if there are any valid single-element results,

// then bisect returns one of them.

func bisect(targets []string, forced []string) []string {

if len(targets) == 1 {

// Reduced list to a single required entry.

return []string{targets[0]}

}

// Split targets in half.

m := len(targets)/2

left, right := targets[:m], targets[m:]

// If either half is sufficient by itself, focus there.

if buggy(slices.Concat(left, forced)) {

return bisect(left, forced)

}

if buggy(slices.Concat(right, forced)) {

return bisect(right, forced)

}

// Otherwise need parts of both halves.

leftReduced := bisect(left, slices.Concat(right, forced))

rightReduced := bisect(right, slices.Concat(leftReduced, forced))

return slices.Concat(leftReduced, rightReduced)

}

The easy/hard algorithm has two benefits and one drawback compared to the short algorithm.

One benefit is that the easy/hard algorithm more directly maps to our intuitions about what bisecting should do: try one side, try the other, fall back to some combination of both sides. In contrast, the short algorithm always relies on the general case and is harder to understand.

Another benefit of the easy/hard algorithm is that

it guarantees to find a single-culprit answer when one exists.

Since most bugs can be reduced to a single culprit,

guaranteeing to find one when one exists makes for

easier debugging sessions.

Supposing that optimizing tan would have triggered

the test failure,

the easy/hard algorithm would try

buggy([add cos div exp mod]) = false // left buggy([mul sin sqr sub tan]) = true // right

and then would discard the left side, focusing on the right side

and eventually finding [tan], instead of [sin cos].

The drawback is that because the easy/hard algorithm doesn’t often rely

on the general case, the general case needs more careful testing

and is easier to get wrong without noticing.

For example, Andreas Zeller’s 1999 paper

“Yesterday, my program worked. Today, it does not. Why?”

gives what should be the easy/hard version of the bisect-reduce algorithm

as a way to bisect over independent program changes,

except that the algorithm has a bug:

in the “hard” case, the right bisection forces left instead of leftReduced.

The result is that if there are two culprit pairs crossing

the left/right boundary, the reductions can

choose one culprit from each pair instead of a matched pair.

Simple test cases are all handled by the easy case, masking the bug.

In contrast, if we insert the same bug into the general case of the short algorithm,

very simple test cases fail.

Real implementations are better served by the easy/hard algorithm,

but they must take care to implement it correctly.

List-Based Bisect-Reduce

Having established the algorithm, let’s now turn to the details of hooking it up to a compiler. Exactly how do we obtain the list of source locations, and how do we feed it back into the compiler?

The most direct answer is to implement one debug mode

that prints the full list of locations for the optimization

in question

and another debug mode that accepts a list

indicating where the optimization is permitted.

Meta’s Cinder JIT for Python,

published in 2021,

takes this approach for deciding which functions to compile with the JIT

(as opposed to interpret).

Its Tools/scripts/jitlist_bisect.py

is the earliest correct published version of the bisect-reduce algorithm

that I’m aware of,

using the easy/hard form.

The only downside to this approach is the potential size of the lists,

especially since bisect debugging is critical for reducing

failures in very large programs.

If there is some way to reduce the amount of data that must be

sent back to the compiler on each iteration, that would be helpful.

In complex build systems, the function lists may be too large

to pass on the command line or in an environment variable,

and it may be difficult or even impossible to arrange for a new input file

to be passed to every compiler invocation.

An approach that can specify the target list as a short command line argument

will be easier to use in practice.

Counter-Based Bisect-Reduce

Java’s HotSpot C2 just-in-time (JIT) compiler provided a

debug mechanism to control which functions to compile with the JIT,

but instead of using an explicit list of functions like in Cinder,

HotSpot numbered the functions as it considered them.

The compiler flags -XX:CIStart and -XX:CIStop set the

range of function numbers that were eligible to be compiled.

Those flags are

still present today (in debug builds),

and you can find uses of them in

Java bug reports dating back at least to early 2000.

There are at least two limitations to numbering functions.

The first limitation is minor and easily fixed:

allowing only a single contiguous range

enables binary search for a single culprit but

not the general bisect-reduce for multiple culprits.

To enable bisect-reduce, it would suffice

to accept a list of integer ranges, like -XX:CIAllow=1-5,7-10,12,15.

The second limitation is more serious:

it can be difficult to keep the numbering stable from run to run.

Implementation strategies like compiling functions in parallel

might mean considering functions in varying orders based

on thread interleaving.

In the context of a JIT, even threaded runtime execution

might change the order that functions are considered for compilation.

Twenty-five years ago, threads were rarely used and this limitation may not have been

much of a problem.

Today, assuming a consistent function numbering is a show-stopper.

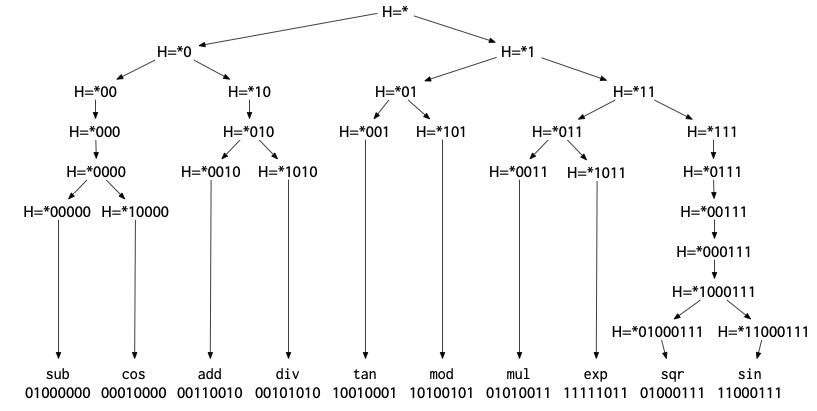

Hash-Based Bisect-Reduce

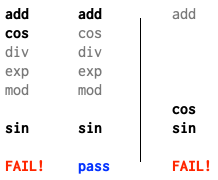

A different way to keep the location list implicit is to hash each location to a (random-looking) integer and then use bit suffixes to identify sets of locations. The hash computation does not depend on the sequence in which the source locations are encountered, making hashing compatible with parallel compilation, thread interleaving, and so on. The hashes effectively arrange the functions into a binary tree:

Looking for a single culprit is a basic walk down the tree.

Even better, the general bisect-reduce algorithm is easily

adapted to hash suffix patterns.

First we have to adjust the definition of buggy:

we need it to tell us the number of matches for the

suffix we are considering, so we know whether

we can stop reducing the case:

// buggy reports whether the bug is triggered // by enabling the change at the locations with // hashes ending in suffix or any of the extra suffixes. // It also returns the number of locations found that // end in suffix (only suffix, ignoring extra). func buggy(suffix string, extra []string) (fail bool, n int)

Now we can translate the easy/hard algorithm more or less directly:

// BisectReduce returns a locally minimal list of hash suffixes,

// each of which uniquely identifies a single location hash,

// such that buggy(list) is true.

func BisectReduce() []string {

if fail, _ := buggy("none", nil); fail {

return nil

}

return bisect("", []string{})

}

// bisect returns a locally minimal list of hash suffixes,

// each of which uniquely identifies a single location hash,

// and all of which end in suffix,

// such that buggy(result+forced) = true.

//

// Precondition: buggy(suffix, forced) = true, _.

// and buggy("none", forced) = false, 0.

//

// Postcondition: buggy("none", result+forced) = true, 0;

// each suffix in result matches a single location hash;

// and buggy("none", x+forced) = false for any x ⊂ result.

// Also, if there are any valid single-element results,

// then bisect returns one of them.

func bisect(suffix string, forced []string) []string {

if _, n := buggy(suffix, forced); n == 1 {

// Suffix identifies a single location.

return []string{suffix}

}

// If either of 0suffix or 1suffix is sufficient

// by itself, focus there.

if fail, _ := buggy("0"+suffix, forced); fail {

return bisect("0"+suffix, forced)

}

if fail, _ := buggy("1"+suffix, forced); fail {

return bisect("1"+suffix, forced)

}

// Matches from both extensions are needed.

// Otherwise need parts of both halves.

leftReduced := bisect("0"+suffix,

slices.Concat([]string{"1"+suffix"}, forced))

rightReduced := bisect("1"+suffix,

slices.Concat(leftReduced, forced))

return slices.Concat(leftReduce, rightReduce)

}

Careful readers might note that in the easy cases,

the recursive call to bisect starts by repeating the same

call to buggy that the caller did,

this time to count the number of matches for the suffix in question.

An efficient implementation could pass the result of that run to

the recursive call, avoiding redundant trials.

In this version, bisect does not guarantee to cut the search space in half

at each level of the recursion.

Instead, the randomness of the hashes means that it cuts the search space

roughly in half on average.

That’s still enough for logarithmic behavior when there are

just a few culprits.

The algorithm would also work correctly if the suffixes were

applied to match a consistent sequential numbering instead of hashes;

the only problem is obtaining the numbering.

The hash suffixes are about as short as the function number ranges

and easily passed on the command line.

For example, a hypothetical Java compiler could use -XX:CIAllowHash=000,10,111.

Use Case: Function Selection

The earliest use of hash-based bisect-reduce in Go was for selecting functions, as in the example we’ve been considering. In 2015, Keith Randall was working on a new SSA backend for the Go compiler. The old and new backends coexisted, and the compiler could use either for any given function in the program being compiled. Keith introduced an environment variable GOSSAHASH that specified the last few binary digits of the hash of function names that should use the new backend: GOSSAHASH=0110 meant “compile only those functions whose names hash to a value with last four bits 0110.” When a test was failing with the new backend, a person debugging the test case tried GOSSAHASH=0 and GOSSAHASH=1 and then used binary search to progressively refine the pattern, narrowing the failure down until only a single function was being compiled with the new backend. This was invaluable for approaching failures in large real-world tests (tests for libraries or production code, not for the compiler) that we had not written and did not understand. The approach assumed that the failure could always be reduced to a single culprit function.

It is fascinating that HotSpot, Cinder, and Go all hit upon the idea

of binary search to find miscompiled functions in a compiler,

and yet all three used different selection mechanisms

(counters, function lists, and hashes).

Use Case: SSA Rewrite Selection

In late 2016, David Chase was debugging a new optimizer rewrite rule that should have been correct but was causing mysterious test failures. He reused the same technique but at finer granularity: the bit pattern now controlled which functions that rewrite rule could be used in.

David also wrote the initial version of a tool, gossahash,

for taking on the job of binary search.

Although gossahash only looked for a single failure, but it was remarkably helpful.

It served for many years and eventually became bisect.

Use Case: Fused Multiply-Add

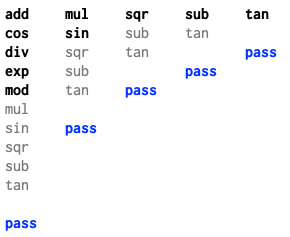

Having a tool available, instead of needing to bisect manually, made us keep finding problems we could solve. In 2022, another presented itself. We had updated the Go compiler to use floating-point fused multiply-add (FMA) instructions on a new architecture, and some tests were failing. By making the FMA rewrite conditional on a suffix of a hash that included the current file name and line number, we could apply bisect-reduce to identify the specific line in the source code where FMA instruction broke the test.

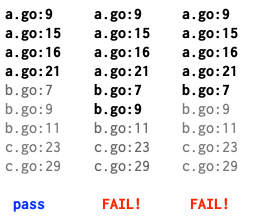

For example, this bisection finds that b.go:7 is the culprit line:

FMA is not something most programmers encounter.

If they do get an FMA-induced test failure, having a tool that automatically

identifies the exact culprit line is invaluable.

Use Case: Language Changes

The next problem that presented itself was a language change. Go, like C# and JavaScript, learned the hard way that loop-scoped loop variables don’t mix well with closures and concurrency. Like those languages, Go recently changed to iteration-scoped loop variables, correcting many buggy programs in the process.

Unfortunately, sometimes tests unintentionally check for buggy behavior. Deploying the loop change in a large code base, we confronted truly mysterious failures in complex, unfamiliar code. Conditioning the loop change on a suffix of a hash of the source file name and line number enabled bisect-reduce to pinpoint the specific loop or loops that triggered the test failures. We even found a few cases where changing any one loop did not cause a failure, but changing a specific pair of loops did. The generality of finding multiple culprits is necessary in practice.

The loop change would have been far more difficult without

automated diagnosis.

Use Case: Library Changes

Bisect-reduce also applies to library changes: we can hash the caller, or more precisely the call stack, and then choose between the old and new implementation based on a hash suffix.

For example, suppose you add a new sort implementation and a large program fails. Assuming the sort is correct, the problem is almost certainly that the new sort and the old sort disagree about the final order of some values that compare equal. Or maybe the sort is buggy. Either way, the large program probably calls sort in many different places. Running bisect-reduce over hashes of the call stacks will identify the exact call stack where using the new sort causes a failure. This is what was happening in the example at the start of the post, with a new timer implementation instead of a new sort.

Call stacks are a use case that only works with hashing, not with sequential numbering. For the examples up to this point, a setup pass could number all the functions in a program or number all the source lines presented to the compiler, and then bisect-reduce could apply to binary suffixes of the sequence number. But there is no dense sequential numbering of all the possible call stacks a program will encounter. On the other hand, hashing a list of program counters is trivial.

We realized that bisect-reduce would apply to library changes

around the time we were introducing the

GODEBUG mechanism,

which provides a framework for tracking and toggling these kinds of

compatible-but-breaking changes.

We arranged for that framework to provide bisect support for all

GODEBUG settings automatically.

For Go 1.23, we rewrote the time.Timer

implementation and changed its semantics slightly,

to remove some races in existing APIs

and also enable earlier garbage collection in some common cases.

One effect of the new implementation is that very short timers trigger more reliably.

Before, a 0ns or 1ns timer (which are often used in tests) could take

many microseconds to trigger.

Now, they trigger on time.

But of course, buggy code (mostly in tests) exists that fails

when the timers start triggering as early as they should.

We debugged a dozen or so of these inside Google’s source tree—all of them complex and unfamiliar—and

bisect made the process painless and maybe even fun.

For one failing test case, I made a mistake.

The test looked simple enough to eyeball, so I spent

half an hour puzzling through how the only timer in the code under test,

a hard-coded one minute timer,

could possibly be affected by the new implementation.

Eventually I gave up and ran bisect.

The stack trace showed immediately that there was a testing middleware layer that

was rewriting the one-minute timeout

into a 1ns timeout to speed the test.

Tools see what people cannot.

Interesting Lessons Learned

One interesting thing we learned while working on bisect is that it is

important to try to detect flaky tests.

Early in debugging loop change failures,

bisect pointed at a completely correct, trivial loop in a cryptography package.

At first, we were very scared: if that loop was changing behavior,

something would have to be very wrong in the compiler.

We realized the problem was flaky tests. A test that fails randomly

causes bisect to make a random walk over the source code,

eventually pointing a finger at entirely innocent code.

After that, we added a -count=N flag to bisect that causes it

to run every trial N times and bail out entirely if they disagree.

We set the default to -count=2 so that bisect always does basic

flakiness checking.

Flaky tests remain an area that needs more work. If the problem being debugged

is that a test went from passing reliably to failing half the time,

running go test -count=5 increases the chance of failure by running the test five times.

Equivalently, it can help to use a tiny shell script like

% cat bin/allpass

#!/bin/sh

n=$1

shift

for i in $(seq $n); do

"$@" || exit 1

done

Then bisect can be invoked as:

% bisect -godebug=timer allpass 5 ./flakytest

Now bisect only sees ./flakytest passing five times in a row as a successful run.

Similarly, if a test goes from passing unreliably to failing all the time,

an anypass variant works instead:

% cat bin/anypass

#!/bin/sh

n=$1

shift

for i in $(seq $n); do

"$@" && exit 0

done

exit 1

The timeout command

is also useful if the change has made a test run forever instead of failing.

The tool-based approach to handling flakiness works decently

but does not seem like a complete solution.

A more principled approach inside bisect would be better.

We are still working out what that would be.

Another interesting thing we learned is that when bisecting over

run-time changes, hash decisions are made so frequently that

it is too expensive to print the full stack trace of every decision

made at every stage of the bisect-reduce,

(The first run uses an empty suffix that matches every hash!)

Instead, bisect hash patterns default to a “quiet” mode where each

decision prints only the hash bits, since that’s all bisect needs

to guide the search and narrow down the relevant stacks.

Once bisect has identified a minimal set of relevant stacks,

it runs the test once more with the hash pattern in “verbose” mode.

That causes the bisect library to print both the hash bits

and the corresponding stack traces,

and bisect displays those stack traces in its report.

Try Bisect

The bisect tool

can be downloaded and used today:

% go install golang.org/x/tools/cmd/bisect@latest

If you are debugging a loop variable problem in Go 1.22, you can use a command like

% bisect -compile=loopvar go test

If you are debugging a timer problem in Go 1.23, you can use:

% bisect -godebug asynctimerchan=1 go test

The -compile and -godebug flags are conveniences.

The general form of the command is

% bisect [KEY=value...] cmd [args...]

where the leading KEY=value arguments set environment variables

before invoking the command with the remaining arguments.

Bisect expects to find the literal string PATTERN somewhere

on its command line, and it replaces that string with a hash pattern

each time it repeats the command.

You can use bisect to debug problems in your own compilers or libraries

by having them accept a hash pattern either in the environment or on

the command line and then print specially formatted lines for bisect

on standard output or standard error.

The easiest way to do this is to use

the bisect package.

That package is not available for direct import yet

(there is a pending proposal to add it to the Go standard library),

but the package is only a single file with no imports,

so it is easily copied into new projects or even translated to other languages.

The package documentation also documents the hash pattern syntax

and required output format.

If you work on compilers or libraries and ever need to debug why

a seemingly correct change you made broke a complex program,

give bisect a try.

It never stops feeling like magic.