Floating-Point Printing and Parsing Can Be Simple And Fast

(Floating Point Formatting, Part 3)

Russ Cox

January 19, 2026

research.swtch.com/fp

Posted on Monday, January 19, 2026.

PDF

January 19, 2026

research.swtch.com/fp

Introduction

A floating point number has the form where is called the mantissa and is a signed integer exponent. We like to read numbers scaled by powers of ten, not two, so computers need algorithms to convert binary floating-point to and from decimal text. My 2011 post “Floating Point to Decimal Conversion is Easy” argued that these conversions can be simple as long as you don’t care about them being fast. But I was wrong: fast converters can be simple too, and this post shows how.

The main idea of this post is to implement fast unrounded scaling, which computes an approximation to , often in a single 64-bit multiplication. On that foundation we can build nearly trivial printing and parsing algorithms that run very fast. In fact, the printing algorithms run faster than all other known algorithms, including Dragon4 [39], Grisu3 [29], Errol3 [4], Ryū [2], Ryū Printf [3], Schubfach [13], and Dragonbox [18], and the parsing algorithm runs faster than the Eisel-Lemire algorithm [28]. This post presents both the algorithms and a concrete implementation in Go. I expect some form of this Go code to ship in Go 1.27 (scheduled for August 2026).

This post is rather long—far longer than the implementations!—so here is a brief overview of the sections for easier navigation and understanding where we’re headed.

- “Fixed-Point and Floating-Point Numbers” briefly reviews fixed-point and floating-point numbers, establishing some terminology and concepts needed for the rest of the post.

- “Unrounded Numbers” introduces the idea of unrounded numbers, inspired by the IEEE754 floating-point extended format.

- “Unrounded Scaling” defines the unrounded scaling primitive.

- “Fixed-Width Printing” formats floating-point numbers with a given (fixed) number of decimal digits, at most 18.

- “Parsing Decimals” parses decimal numbers of at most 19 digits into floating-point numbers.

- “Shortest-Width Printing” formats floating-point numbers using the shortest representation that parses back to the original number.

- “Fast Unrounded Scaling” reveals the short but subtle implementation of fast unrounded scaling that enables those simple algorithms.

- “Sketch of a Proof of Fast Scaling” briefly sketches the proof that the fast unrounded scaling algorithm is correct. A companion post, “Fast Unrounded Scaling: Proof by Ivy” provides the full details.

- “Omit Needless Multiplications” uses a key idea from the proof to optimize the fast unrounded scaling implementation further, reducing it to a single 64-bit multiplication in many cases.

- “Performance” compares the performance of the implementation of these algorithms against earlier ones.

- “History and Related Work” examines the history of solutions to the floating-point printing and parsing problems and traces the origins of the specific ideas used in this post’s algorithms.

For the last decade, there has been a new algorithm for floating-point printing and parsing

every few years.

Given the simplicity and speed of the algorithms in this post

and the increasingly small deltas between successive algorithms,

perhaps we are nearing an optimal solution.

Fixed-Point and Floating-Point Numbers

Fixed-point numbers have the form for an integer mantissa , constant base , and constant (fixed) exponent . We can create fixed-point representations in any base, but the most common are base 2 (for computers) and base 10 (for people). This diagram shows fixed-point numbers at various scales that can represent numbers between 0 and 1:

Using a smaller scaling factor increases precision at the cost of larger mantissas. When representing very large numbers, we can use larger scaling factors to reduce the mantissa size. For example, here are various representations of numbers around one billion:

Floating-point numbers are the same as base-2 fixed-point numbers except that changes with the overall size of the number. Small numbers use very small scaling factors while large numbers use large scaling factors, aiming to keep the mantissas a constant length. For float64s, the exponent is chosen so that the mantissa has 53 bits, meaning . For example, for numbers in , float64s use ; for numbers in they use ; and so on.

[The notation is a half-open interval, which includes but not . In contrast, the closed interval includes both and . We write or to say that is in that interval. Using this notation, means .]

In addition to limiting the mantissa size, we must also limit the exponent, to keep the overall number a fixed size. For float64s, assuming , the exponent .

A float64 consists of 1 sign bit, 11 exponent bits, and 52 mantissa bits.

The normal 11-bit exponent encodings 0x001 through 0x3fe denote through .

For those, the mantissa ,

and it is encoded into only 52 bits by omitting the leading 1 bit.

The special exponent encoding 0x3ff is used for infinity and not-a-number.

That leaves the encoding 0x000, which is also special.

It denotes (like 0x001 does)

but with mantissas without an implicit leading 1.

These subnormals or denormalized numbers [9]

continue the fixed-point scale down to zero,

which ends up encoded (not coincidentally) as 64 zero bits.

Other definitions of floating point numbers use different interpretations. For example the IEEE754 standard uses with , while the C standard libary frexp function uses with . Both of these choices make itself a fixed-point number instead of an integer. Our integer definition lets us use integer math. These interpretations are all equivalent and differ only by a constant added to .

This description of float64s applies to float32s as well, but with different constants. This table summarizes the two encodings:

| float32 | float64 | |

|---|---|---|

| sign bits | 1 | 1 |

| encoded mantissa bits | 23 | 52 |

| encoded exponent bits | 8 | 11 |

| exponent range for | ||

| exponent range for integer | ||

| normal numbers | ||

| subnormal numbers | ||

| exponent range for 64-bit | ||

| normal numbers | ||

| subnormal numbers |

To convert a float64 to its bits, we use Go’s math.Float64bits.

// unpack64 returns m, e such that f = m * 2**e. // The caller is expected to have handled 0, NaN, and ±Inf already. // To unpack a float32 f, use unpack64(float64(f)). func unpack64(f float64) (uint64, int) { const shift = 64 - 53 const minExp = -(1074 + shift) b := math.Float64bits(f) m := 1<<63 | (b&(1<<52-1))<<shift e := int((b >> 52) & (1<<shift - 1)) if e == 0 { m &^= 1 << 63 e = minExp s := 64 - bits.Len64(m) return m << s, e - s } return m, (e - 1) + minExp }

To convert back, we use Go’s math.Float64frombits.

// pack64 takes m, e and returns f = m * 2**e. // It assumes the caller has provided a 53-bit mantissa m // and an exponent that is in range for the mantissa. func pack64(m uint64, e int) float64 { if m&(1<<52) == 0 { return math.Float64frombits(m) } return math.Float64frombits(m&^(1<<52) | uint64(1075+e)<<52) }

[Other presentations use “fraction” and “significand” instead of “mantissa”.

This post uses mantissa for consistency with my 2011 post

and because I generally agree with Agatha Mallett’s excellent

“In Defense of ‘Mantissa’”.]

Unrounded Numbers

Floating-point operations are defined as if computed exactly to infinite precision and then rounded to the nearest actual floating-point number, breaking ties by rounding to an even mantissa. Of course, real implementations don’t use infinite precision; they only keep enough precision to round properly. We will use the same idea. In our algorithms, we want the scaling operation to eventually evaluate to an integer, but we want to give the caller control over the rounding step. So instead of returning an integer, we will return an unrounded number, which contains all the information needed to round it in a variety of ways.

The unrounded form of any real number , which we will write as as , is the truncated integer part of followed by two more bits. Those bits indicate (1) whether the fractional part of was at least ½, and (2) whether the fractional part was not exactly 0 or ½. If you think of as a real number written in binary, the first extra bit is the bit immediately after the “binary point”—the bit that represents , aka the ½ bit—and the second extra bit is the OR of all the bits after the ½ bit.

This definition applies even to numbers that require an infinite binary representation. For example, just as 1/3 requires an infinite decimal representation ‘’, 1.6 requires an infinite binary representation ‘’. The unrounded version is finite: ‘’. But instead of reading unrounded numbers in binary, let’s print as where is the integer part , is 0 or 5, and is ‘+’ when the second bit is 1. Then is written ‘’.

Let’s implement unrounded numbers in Go.

type unrounded uint64

func unround(x float64) unrounded {

return unrounded(math.Floor(4*x)) | bool2[unrounded](math.Floor(4*x) != 4*x)

}

func (u unrounded) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("⟨%d.%d%s⟩", u>>2, 5*((u>>1)&1), "+"[1-u&1:])

}

The bool2 function converts a boolean to an integer.

(The Go compiler will implement this using an inlined conditional move.)

// bool2 converts b to an integer: 1 for true, 0 for false.

func bool2[T ~int | ~uint64](b bool) T {

if b {

return 1

}

return 0

}

We won’t use the unround constructor in our actual code, but it’s helpful for playing.

For example, we can try the examples we just saw:

row("x", "raw", "str")

for _, x := range []float64{6, 6.001, 6.499, 6.5, 6.501, 6.999, 7} {

u := unround(x)

row(x, uint64(u), u)

}

table()

x raw str 6 24 ⟨6.0⟩ 6.001 25 ⟨6.0+⟩ 6.499 25 ⟨6.0+⟩ 6.5 26 ⟨6.5⟩ 6.501 27 ⟨6.5+⟩ 6.999 27 ⟨6.5+⟩ 7 28 ⟨7.0⟩

The unrounded form holds the information needed by all the usual rounding operations. Adding 0, 1, 2, or 3 and then dividing by four (or shifting right by two) yields: floor, round with ½ rounding down, round with ½ rounding up, and ceiling. In floating-point math, we want to round with ½ rounding to even, meaning 1½ and 2½ both round to 2. We can do that by adding , where is 0 or 1 according to whether is odd. That’s just the low bit of : .

Putting that all together:

In Go:

func (u unrounded) floor() uint64 { return uint64((u + 0) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) roundHalfDown() uint64 { return uint64((u + 1) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) round() uint64 { return uint64((u + 1 + (u>>2)&1) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) roundHalfUp() uint64 { return uint64((u + 2) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) ceil() uint64 { return uint64((u + 3) >> 2) }row("x", "floor", "round½↓", "round", "round½↑", "ceil")

for _, x := range []float64{6, 6.25, 6.5, 6.75, 7, 7.5, 8.5} {

u := unround(x)

row(u, u.floor(), u.roundHalfDown(), u.round(), u.roundHalfUp(), u.ceil())

}

table()

x floor round½↓ round round½↑ ceil ⟨6.0⟩ 6 6 6 6 6 ⟨6.0+⟩ 6 6 6 6 7 ⟨6.5⟩ 6 6 6 7 7 ⟨6.5+⟩ 6 7 7 7 7 ⟨7.0⟩ 7 7 7 7 7 ⟨7.5⟩ 7 7 8 8 8 ⟨8.5⟩ 8 8 8 9 9

Dividing unrounded numbers preserves correct rounding as long as the second extra bit is maintained correctly: once it is set to 1, it has to stay a 1 in all future results. This gives the second extra bit its shorter name: the sticky bit.

To divide an unrounded number, we do a normal divide but force the sticky bit to 1 when there is a remainder. Right shift does the same.

For example, if we rounded 15.4 to an integer 15 and then divided it by 6, we’d get 2.5, which rounds down to 2, but the more precise answer would be 15.4/6 = 2.57, which rounds up to 3. An unrounded division handles this correctly:

Let’s implement division and right shift in Go:

func (u unrounded) div(d uint64) unrounded {

x := uint64(u)

return unrounded(x/d) | u&1 | bool2[unrounded](x%d != 0)

}

func (u unrounded) rsh(s int) unrounded {

return u>>s | u&1 | bool2[unrounded](u&((1<<s)-1) != 0)

}u := unround(15.1).div(6) fmt.Println(u, u.round())

⟨2.5+⟩ 3

Finally, we are going to need to be able to nudge an unrounded number up or down before computing a ceiling or floor, as if we added or subtracting a tiny amount. Let’s add that:

func (u unrounded) nudge(δ int) unrounded { return u + unrounded(δ) }row("x", "nudge(-1).floor", "floor", "ceil", "nudge(+1).ceil")

for _, x := range []float64{15, 15.1, 15.9, 16} {

u := unround(x)

row(u, u.nudge(-1).floor(), u.floor(), u.ceil(), u.nudge(+1).ceil())

}

x nudge(-1).floor floor ceil nudge(+1).ceil ⟨15.0⟩ 14 15 15 16 ⟨15.0+⟩ 15 15 16 16 ⟨15.5+⟩ 15 15 16 16 ⟨16.0⟩ 15 16 16 17

Floating-point hardware maintains three extra bits to round

all arithmetic operations correctly.

For just division and right shift, we can get by with only two bits.

Unrounded Scaling

The fundamental insight of this post is that all floating-point conversions can be written correctly and simply using unrounded scaling, which multiplies a number by a power of two and a power of ten and returns the unrounded product.

When is negative, the value cannot be stored exactly in any finite binary floating-point number, so any implementation of uscale must be careful.

In Go, we can implement uscale using big integers and an unrounded division:

func uscale(x uint64, e, p int) unrounded {

num := mul(big(4), big(x), pow(2, max(0, p)), pow(10, max(0, e)))

denom := mul( pow(2, max(0, -p)), pow(10, max(0, -e)))

div, mod := divmod(num, denom)

return unrounded(div.uint64() | bool2[uint64](!mod.isZero()))

}

The max expressions choose between multiplying into num when

or multiplying into denom when ,

and similarly for .

The divmod implements the floor, and mod.isZero reports

whether the floor was exact.

This implementation of uscale is correct but inefficient. In our usage, and will mostly cancel out, typically with opposite signs, and the input and result , will always fit in 64 bits. That limited input domain and range makes it possible to implement a very fast, completely accurate uscale, and we’ll see that implementation later.

Our actual implementation will be split into two functions,

to allow sharing some computations derived from and .

Instead of uscale(x, e, p), the fast Go version will be called as uscale(x, prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p))).

Also, callers are responsible for passing in an left-shifted to have its

high bit set.

The unpack function we looked at already arranged that for its result,

but otherwise callers need to do something like:

shift = 64 - bits.Len64(x) ... uscale(x<<shift, prescale(e-shift, p, log2Pow10(p))) ...

Conceptually, uscale maps numbers on one fixed-point scale to numbers on another, including converting between binary and decimal scales. For example, consider the scales and :

Given from the side,

maps to the equivalent

point on the side;

and given from the ,

maps to the equivalent

point on the side.

Before we look at the fast implementation of ,

let’s look at how it simplifies all the floating-point printing

and parsing algorithms.

Fixed-Width Printing

Our first application of uscale is fixed-width printing. Given , we want to compute its approximate equivalent , where has exactly digits. It only takes 17 digits to uniquely identify any float64, so we’re willing to limit , which will ensure fits in a uint64. The strategy is to multiply by for some and then round it to an integer . Then the result is .

The -digit requirement means . From this we can derive :

It is okay for to be too big—we will get an extra digit that we can divide away—so we can approximate as , where is the bit length of . That gives us . With this derivation of , uscale does the rest of the work.

The floor expression is a simple linear function and can be computed exactly for our inputs using fixed-point arithmetic:

// log10Pow2(x) returns ⌊log₁₀ 2**x⌋ = ⌊x * log₁₀ 2⌋. func log10Pow2(x int) int { // log₁₀ 2 ≈ 0.30102999566 ≈ 78913 / 2^18 return (x * 78913) >> 18 }

The log2Pow10 function, which we mentioned above and need to

use when calling prescale, is similar:

// log2Pow10(x) returns ⌊log₂ 10**x⌋ = ⌊x * log₂ 10⌋. func log2Pow10(x int) int { // log₂ 10 ≈ 3.32192809489 ≈ 108853 / 2^15 return (x * 108853) >> 15 }

Now we can put everything together:

// FixedWidth returns the n-digit decimal form of f as d * 10**p. // n can be at most 18. func FixedWidth(f float64, n int) (d uint64, p int) { if n > 18 { panic("too many digits") } m, e := unpack64(f) p = n - 1 - log10Pow2(e+63) u := uscale(m, prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p))) d = u.round() if d >= uint64pow10[n] { d, p = u.div(10).round(), p-1 } return d, -p }

That’s the entire conversion!

The code splits into , ;

computes as just described;

and then uses uscale and round to compute

.

If the result has an extra digit,

either because our approximate log made too big,

or because of rollover during rounding,

we divide the unrounded form by 10, round again, and update .

When we approximated by counting bits,

we used the exact log of the greatest power of two less than or equal to ,

so the computed must be less than twice the intended limit ,

meaning the leading digit (if there are too many digits) must be 1.

And rollover only happens for ‘’,

so it is not possible to have both an extra digit and rollover.

As an example conversion, consider a float64 approximation of () to 15 decimal digits. We have , , and , so .

The and scales align like this:

Then returns the unrounded number ‘314159265358979.0+’,

which rounds to 314159265358979.

Our answer is then .

Parsing Decimals

Unrounded scaling also lets us parse decimal representations of floating-point numbers efficiently. Let’s assume we’ve taken care of parsing a string like ‘1.23e45’ and now have an integer and exponent like , . To convert to a float64, we can choose an appropriate so that and then return .

The derivation of is similar to the derivation of for printing:

Once again, it is okay to overestimate , so we can approximate , yielding . If is very large, will be very small, meaning we will be creating a subnormal, so we need to round to a smaller number of bits. To handle this, we cap at 1074, which caps at . As before, due to the approximation of , the scaled result is at most twice as large as our target, meaning it might have one extra bit to shift away.

// Parse rounds d * 10**p to the nearest float64 f. // d can have at most 19 digits. func Parse(d uint64, p int) float64 { if d > 1e19 { panic("too many digits") } b := bits.Len64(d) e := min(1074, 53-b-log2Pow10(p)) u := uscale(d<<(64-b), prescale(e-(64-b), p, log2Pow10(p))) m := u.round() if m >= 1<<53 { m, e = u.rsh(1).round(), e-1 } return pack64(m, -e) }

FixedWidth and Parse demonstrate

exactly how similar printing and parsing really are.

In printing, we are given , and

find ; then converts binary to decimal.

In parsing, we are given , and find ;

then converts decimal to binary.

We can make parsing a little faster with a few hand optimizations.

This optimized version introduces lp to avoid calling log2Pow10 twice,

and it implements the extra digit handling in branch-free code.

// Parse rounds d * 10**p to the nearest float64 f. // d can have at most 19 digits. func Parse(d uint64, p int) float64 { if d > 1e19 { panic("too many digits") } b := bits.Len64(d) lp := log2Pow10(p) e := min(1074, 53-b-lp) u := uscale(d<<(64-b), prescale(e-(64-b), p, lp)) // This block is branch-free code for: // if u.round() >= 1<<53 { // u = u.rsh(1) // e = e - 1 // } s := bool2[int](u >= unmin(1<<53)) u = (u >> s) | u&1 e = e - s return pack64(u.round(), -e) } // unmin returns the minimum unrounded that rounds to x. func unmin(x uint64) unrounded { return unrounded(x<<2 - 2) }

Now we are ready for our next challenge: shortest-width printing.

Shortest-Width Printing

Shortest-width printing means to prepare a decimal representation

that a floating-point parser would convert back to the exact same float64,

using as few digits as possible.

When there are multiple possible shortest decimal outputs,

we insist on the one that is nearest the original input,

namely the correctly-rounded one.

In general, 17 digits are always enough to uniquely identify a float64,

but sometimes fewer can be used, even down to a single digit in numbers like 1, 2e10, and 3e−42.

An obvious approach would be to use FixedPrint for increasing values of n,

stopping when Parse(FixedPrint(f, n)) == f.

Or maybe we should derive an equation for n and then use FixedPrint(f, n) directly.

Surprisingly, neither approach works:

Short(f) is not necessarily FixedPrint(f, n) for some n.

The simplest demonstration of this is ,

which looks like this:

Because is a power of two, the floating-point exponent changes at , as does the spacing between floating-point numbers. The next smallest value is , marked on the diagram as . The dotted lines mark the halfway points between and its nearest floating point neighbors. The accurate decimal answers are those at or between the dotted lines, all of which convert back to .

The correct rounding of to 16 digits ends in …901: the next digit in is 3,

so we should round down.

However, because of the spacing change around ,

that correct decimal rounding does not convert back to .

A FixedPrint loop would choose a 17-digit form instead.

But there is an accurate 16-digit form, namely …902.

That decimal is closer to than it is to any other float64,

making it an accurate .

And since the closer 16-digit value …901 is not an accurate ,

Short should use …902 instead.

Assuming as usual that , let’s define to be the distance between the midpoints from to its floating-point neighbors. Normally those neighbors are in either direction—the midpoints are —so . At a power of two with an exponent change, the lower midpoint is instead , so . The rounding paradox can only happen for powers of two with this kind of skewed footprint.

All that is to say we cannot use FixedWidth with “the right ”.

But we can use scale directly with “the right .”

Specifically, we can compute the midpoints between

and its floating-point neighbors

and scale them to obtain the

minimum and maximum valid choices for .

Then we can make the best choice:

-

If one of the valid ends in 0, use it after removing trailing zeros.

(Choosing the right will allow at most ten consecutive integers, so at most will one end in 0.) - If there is only one valid , use it.

- Otherwise there are at least two valid , at least one on each side of ; use the correctly rounded one.

Here is an example of the first case: one of the valid ends in zero.

We already saw an example of the second case: only one valid . For numbers with symmetric footprints, that will be the correctly rounded . As we saw for numbers with skewed footprints, that may not be the correctly rounded , but it is still the correct answer.

Finally, here is an example of the third case: multiple valid , but none that end in zero. Now we should use the correctly rounded one.

This sounds great, but how do we determine the right ? We want to allow at least one decimal integer, but at most ten, meaning . Luckily, we can hit that target exactly.

For a symmetric footprint:

For a skewed footprint:

For the symmetric footprint, we can use log10Pow2,

but for the skewed footprint, we need a new approximation:

// skewed computes the skewed footprint of m * 2**e, // which is ⌊log₁₀ 3/4 * 2**e⌋ = ⌊e*(log₁₀ 2)-(log₁₀ 4/3)⌋. func skewed(e int) int { return (e*631305 - 261663) >> 21 }

We should worry about a footprint with decimal width exactly 1, since if had an odd mantissa, the midpoints would be excluded. In that case, if the decimals were the exact midpoints, there would be no decimal between them, making the conversion invalid. But it turns out we should not worry too much. For a skewed footprint, can never be exactly 1, because nothing can divide away the 3. For a symmetric footprint, can only happen for , but then scaling is a no-op, so that the decimal integers are exactly the binary integers. The non-integer midpoints map to non-integer decimals.

When we compute the decimal equivalents of the midpoints, we will use ceiling and floor instead of rounding them, to make sure the integer results are valid decimal answers. If the mantissa is odd, we will nudge the unrounded forms inward slightly before taking the ceiling or floor, since rounding will be away from .

The Go code is:

// Short computes the shortest formatting of f, // using as few digits as possible that will still round trip // back to the original float64. func Short(f float64) (d uint64, p int) { const minExp = -1085 m, e := unpack64(f) var min uint64 z := 11 // extra zero bits at bottom of m; 11 for 53-bit m if m == 1<<63 && e > minExp { p = -skewed(e + z) min = m - 1<<(z-2) // min = m - 1/4 * 2**(e+z) } else { if e < minExp { z = 11 + (minExp - e) } p = -log10Pow2(e + z) min = m - 1<<(z-1) // min = m - 1/2 * 2**(e+z) } max := m + 1<<(z-1) // max = m + 1/2 * 2**(e+z) odd := int(m>>z) & 1 pre := prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p)) dmin := uscale(min, pre).nudge(+odd).ceil() dmax := uscale(max, pre).nudge(-odd).floor() if d = dmax / 10; d*10 >= dmin { return trimZeros(d, -(p - 1)) } if d = dmin; d < dmax { d = uscale(m, pre).round() } return d, -p }

Notice that this algorithm requires either two or three calls to uscale.

When the number being printed has only one valid representation

of the shortest length, we avoid the third call to uscale.

Also notice that the prescale result is shared by all three calls.

When , ,

meaning it won’t be left shifted as far as possible

during the call to uscale.

Although we could detect this case and call uscale

with and ,

using unmodified is fine:

it is still shifted enough that the bits uscale

needs to return will stay in the high 64 bits of the 192-bit product,

and using the same

lets us use the same prescale work for all three calls.

Trimming Zeros

The trimZeros function used in Short removes any trailing zeros from its argument,

updating the decimal power. An unoptimized version is:

// trimZeros removes trailing zeros from x * 10**p. // If x ends in k zeros, trimZeros returns x/10**k, p+k. // It assumes that x ends in at most 16 zeros. func trimZeros(x uint64, p int) (uint64, int) { if x%10 != 0 { return x, p } x /= 10 p += 1 if x%100000000 == 0 { x /= 100000000 p += 8 } if x%10000 == 0 { x /= 10000 p += 4 } if x%100 == 0 { x /= 100 p += 2 } if x%10 == 0 { x /= 10 p += 1 } return x, p }

The initial removal of a single zero gives an early return for the common case of having no zeros. Otherwise, the code makes four additional checks that collectively remove up to 16 more zeros. For outputs with many zeros, these four checks run faster than a loop removing one zero at a time.

When compiling this code,

the Go compiler reduces the remainder checks to multiplications

using the following well-known optimization.

An exact uint64 division where

can be implemented by where

is the uint64 multiplicative inverse of , meaning :

Since is also the multiplicative inverse of , is

lossless—all the exact multiples of map to all of —so

the non-multiples are forced to map to larger values.

This observation gives a quick test for whether is an exact multiple of :

check whether .

Only odd have multiplicative inverses modulo powers of two, so even divisors require more work. To compute an exact division , we can use instead. To check for remainder, we need to check that those low bits are all zero before we shift them away. We can merge that check with the range check by rotating those bits into the high part instead of discarding them: check whether , where is right rotate.

The Go compiler does this transformation automatically

for the if conditions in trimZeros,

but inside the if bodies, it does not reuse the

exact quotient it just computed.

I considered changing the compiler to recognize that pattern,

but instead I wrote out the remainder check by hand

in the optimized version, allowing me to reuse the computed exact quotients:

// trimZeros removes trailing zeros from x * 10**p. // If x ends in k zeros, trimZeros returns x/10**k, p+k. // It assumes that x ends in at most 16 zeros. func trimZeros(x uint64, p int) (uint64, int) { const ( maxUint64 = ^uint64(0) inv5p8 = 0xc767074b22e90e21 // inverse of 5**8 inv5p4 = 0xd288ce703afb7e91 // inverse of 5**4 inv5p2 = 0x8f5c28f5c28f5c29 // inverse of 5**2 inv5 = 0xcccccccccccccccd // inverse of 5 ) // Cut 1 zero, or else return. if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5, -1); d <= maxUint64/10 { x = d p += 1 } else { return x, p } // Cut 8 zeros, then 4, then 2, then 1. if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5p8, -8); d <= maxUint64/100000000 { x = d p += 8 } if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5p4, -4); d <= maxUint64/10000 { x = d p += 4 } if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5p2, -2); d <= maxUint64/100 { x = d p += 2 } if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5, -1); d <= maxUint64/10 { x = d p += 1 } return x, p }

This approach to trimming zeros is from Dragonbox.

For more about the general optimization,

see Warren’s Hacker’s Delight [43],

sections 10-16 and 10-17.

Fast, Accurate Scaling

The conversion algorithms we examined are nice and simple.

For them to be fast, uscale needs to be fast while remaining correct.

Although multiplication by can be implemented by shifts,

uscale cannot actually compute or multiply by

—that would take too long when is a large positive or negative number.

Instead, we can approximate as a floating-point number with a 128-bit mantissa,

looked up in a table indexed by .

Specifically, we will use and ,

ensuring that .

We will write a separate program to generate this table.

It emits Go code defining pow10Min, pow10Max, and pow10Tab:

pow10Tab[0] holds the entry for .

To figure out how big the table needs to be,

we can analyze the three functions we just wrote.

-

FixedWidthconverts floating-point to decimal. It needs to calluscalewith a 53-bit , , and . -

Shortalso converts floating-point to decimal. It needs to calluscalewith a 55-bit , , and . -

Parseconverts decimal to floating-point. It needs to calluscalewith a 64-bit and . (Outside that range of ,Parsecan return 0 or infinity.)

So the table needs to provide answers for .

If , then .

In all of our algorithms, the result of uscale was always small—at most 64 bits.

Since is 128 bits and is even bigger, must be negative,

so this computation is

(x*pm) >> -(e+pe).

Because of the ceiling, may be too large by an error ,

so may be too large by an error .

To round exactly, we care whether any of the shifted bits is 1,

but may change the low bits,

so we can’t trust them.

Instead, we will throw them away.

and use only the upper bits to compute our unrounded number.

That is the entire idea!

Now let’s look at the implementation.

The prescale function returns a scaler with and a shift count :

// A scaler holds derived scaling constants for a given e, p pair. type scaler struct { pm pmHiLo s int } // A pmHiLo represents hi<<64 + lo. type pmHiLo struct { hi uint64 lo uint64 }

We want the shift count to reserve two extra bits for the unrounded representation and to apply to the top 64-bit word of the 192-bit product, which gives this formula:

That translates directly to Go:

// prescale returns the scaling constants for e, p. // lp must be log2Pow10(p). func prescale(e, p, lp int) scaler { return scaler{pm: pow10Tab[p-pow10Min], s: -(e + lp + 3)} }

In uscale, since the caller left-justified to 64 bits,

discarding the low bits means discarding the

lowest 64 bits of the product, which we skip computing entirely.

Then we use the middle 64-bit word and the low bits

of the upper word to set the sticky bit in the result.

// uscale returns unround(x * 2**e * 10**p). // The caller should pass c = prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p)) // and should have left-justified x so its high bit is set. func uscale(x uint64, c scaler) unrounded { hi, mid := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.hi) mid2, _ := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.lo) mid, carry := bits.Add64(mid, mid2, 0) hi += carry sticky := bool2[unrounded](mid != 0 || hi&((1<<c.s)-1) != 0) return unrounded(hi>>c.s) | sticky }

It is mind-boggling that this works, but it does.

Of course, you shouldn’t take my word for it.

We have to prove it correct.

Sketch of a Proof of Fast Scaling

To prove that our fast uscale algorithm is correct,

there are three cases: small positive ,

small negative ,

and large .

The actual proof, especially for large ,

is non-trivial,

and the details are quite a detour from

our fast scaling implementations,

so this section only sketches the basic ideas.

For the details, see the accompanying post, “Fast Unrounded Scaling: Proof by Ivy.”

Remember from the previous section that for some . Since , ’s 128 bits need only represent the part; the can always be handled by .

For , fits in the top 64 bits of the 128-bit .

Since is exact,

the only possible error is introduced by discarding the bottom bits.

Since the bottom 64 bits of are zero,

the bits we discard are all zero.

So uscale is correct for small positive .

For ,

is approximating division by (remember that is a positive number!).

The 128-bit approximation is precise enough that when is a

multiple of , only the lowest bits are non-zero;

discarding them keeps the unrounded form exact.

And when is not a multiple of ,

the result has a fractional part that must be at least

away from an integer.

That fractional separation is much larger than the maximum error in the product,

so the high bits saved in the unrounded form are correct;

the fraction is also repeating, so that there is guaranteed

to be a 1 bit to cause the unrounded form to be marked inexact.

So uscale is correct for small negative .

Finally, we must handle large , which always have a non-zero error

and therefore should always return unrounded numbers marked inexact

(with the sticky bit set to 1).

Consider the effect of adding a small error to the idealized “correct” ,

producing .

The error is at most 64 bits.

Adding that error to the 192-bit product can certainly affect

the low 64 bits, and it may also generate a carry out of the low 64

into the middle 64 bits.

The carry turns 1 bits into 0 bits from right to left

until it hits a 0 bit;

that first 0 bit becomes a 1, and the carry stops.

The key insight is that seeing a 1 in the middle bits

is proof that the carry did not reach the high bits,

so the high bits are correct.

(Seeing a 1 in the middle bits also ensures that

the unrounded form is marked inexact, as it must be,

even though we discarded the low bits.)

Using a program backed by careful math, we can analyze all the in our table,

showing that every possible has a 1 in the middle bits.

So uscale is correct for large .

Omit Needless Multiplications

We have a fast and correct uscale, but we can make it faster

now that we understand the importance of carry bits.

The idea is to compute the high 64 bits of the product

and then use it directly whenever possible, avoiding the computation

of the remaining 64 bits at all.

To make this work, we need the high 64 bits to be rounded up,

a ceiling instead of a floor.

So we will change the pmHiLo from representing

to .

// A pmHiLo represents hi<<64 - lo.

type pmHiLo struct {

hi uint64

lo uint64

}The exact computation using this form would be:

hi, mid := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.hi) mid2, lo := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.lo) mid, carry := bits.Sub64(mid, mid2, bool2[uint64](lo > 0)) hi -= carry return unrounded(hi >> c.s) | bool2[unrounded](hi&((1<<c.s)-1) != 0 || mid != 0)

The 128-bit product computed on the first line may be too big by an error of up to , which may or may not affect the high 64 bits; The middle three lines correct the product, possibly subtracting 1 from . Like in the proof sketch, if any of the bottom bits of the approximate is a 1 bit, that 1 bit would stop the subtracted carry from affecting the higher bits, indicating that we don’t need to correct the product.

Using this insight, the optimized uscale is:

// uscale returns unround(x * 2**e * 10**p). // The caller should pass c = prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p)) // and should have left-justified x so its high bit is set. func uscale(x uint64, c scaler) unrounded { hi, mid := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.hi) sticky := uint64(1) if hi&(1<<(c.s&63)-1) == 0 { mid2, _ := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.lo) sticky = bool2[uint64](mid-mid2 > 1) hi -= bool2[uint64](mid < mid2) } return unrounded(hi>>c.s | sticky) }

The fix-up looks different from the exact computation above but it has the same effect. We don’t need the actual final value of , only the carry and its effect on the sticky bit.

On some systems, notably x86-64, bits.Mul64 computes both results in a single instruction.

On other systems, notably ARM64, bits.Mul64 must use two different instructions;

it helps on those systems to write the code this way,

optimizing away the computation for the low half of .

The more bits that are being shifted out of hi,

the more likely it is that a 1 bit is being shifted out,

so that we have an answer after only the first bits.Mul64.

When Short calls uscale, it passes two that

differ only in a single bit

and multiplies them by the same .

While one of them might clear the low bits of ,

the other is unlikely to also clear them,

so we are likely to hit the fast path at least once,

if not twice.

In the case where Short calls uscale three times,

we are likely to hit the fast path at least twice.

This optimization means that, most of the time, a uscale

is implemented by a single wide multiply.

This is the main reason that Short runs faster than

Ryū, Schubfach, and Dragonbox, as we will see in the next section.

Performance

I promised these algorithms would be simple and fast. I hope you are convinced about simple. (If not, keep in mind that the implementations in widespread use today are far more complicated!) Now it is time to evaluate ‘fast’ by comparing against other implementations. All the other implementations are written in C or C++ and compiled by a C/C++ compiler. To isolate compilation differences, I translated the Go code to C and measured both the Go code and the C translation.

I ran the benchmarks on two systems.

- Apple M4 (2025 MacBook Air ‘Mac16,12’), 32 GB RAM, macOS 26.1, Apple clang 17.0.0 (clang-1700.6.3.2)

- AMD Ryzen 9 7950X, 128 GB RAM, Linux 6.17.9 and libc6 2.39-0ubuntu8.6, Ubuntu clang 18.1.3 (1ubuntu1)

Both systems used Go 1.26rc1.

The full benchmark code is in the rsc.io/fpfmt package.

Printing Text

Real implementations generate strings, so we need to write code to convert the integers we have been returning into digit sequences, like this:

// formatBase10 formats the decimal representation of u into a. // The caller is responsible for ensuring that a is big enough to hold u. // If a is too big, leading zeros will be filled in as needed. func formatBase10(a []byte, u uint64) { for nd := len(a) - 1; nd >= 0; nd-- { a[nd] = byte(u%10 + '0') u /= 10 } }

Unfortunately, if we connect our fast FixedWidth and Short to this

version of formatBase10, benchmarks spend most of their time in the formatting loop.

There are a variety of clever ways to speed up digit formatting.

For our purposes, it suffices to use the old trick of

splitting the number into two-digit chunks and

then converting each chunk by

indexing a 200-byte lookup table (more precisely, a “lookup string”) of all 2-digit values from 00 to 99:

// i2a is the formatting of 00..99 concatenated, // a lookup table for formatting [0, 99]. const i2a = "00010203040506070809" + "10111213141516171819" + "20212223242526272829" + "30313233343536373839" + "40414243444546474849" + "50515253545556575859" + "60616263646566676869" + "70717273747576777879" + "80818283848586878889" + "90919293949596979899"

Using this table and unrolling the loop to allow the

compiler to optimize away bounds checks, we end up with formatBase10:

// formatBase10 formats the decimal representation of u into a. // The caller is responsible for ensuring that a is big enough to hold u. // If a is too big, leading zeros will be filled in as needed. func formatBase10(a []byte, u uint64) { nd := len(a) for nd >= 8 { // Format last 8 digits (4 pairs). x3210 := uint32(u % 1e8) u /= 1e8 x32, x10 := x3210/1e4, x3210%1e4 x1, x0 := (x10/100)*2, (x10%100)*2 x3, x2 := (x32/100)*2, (x32%100)*2 a[nd-1], a[nd-2] = i2a[x0+1], i2a[x0] a[nd-3], a[nd-4] = i2a[x1+1], i2a[x1] a[nd-5], a[nd-6] = i2a[x2+1], i2a[x2] a[nd-7], a[nd-8] = i2a[x3+1], i2a[x3] nd -= 8 } x := uint32(u) if nd >= 4 { // Format last 4 digits (2 pairs). x10 := x % 1e4 x /= 1e4 x1, x0 := (x10/100)*2, (x10%100)*2 a[nd-1], a[nd-2] = i2a[x0+1], i2a[x0] a[nd-3], a[nd-4] = i2a[x1+1], i2a[x1] nd -= 4 } if nd >= 2 { // Format last 2 digits. x0 := (x % 1e2) * 2 x /= 1e2 a[nd-1], a[nd-2] = i2a[x0+1], i2a[x0] nd -= 2 } if nd > 0 { // Format final digit. a[0] = byte('0' + x) } }

This is more code than I’d prefer, but it is at least straightforward. I’ve seen much more complex versions.

With formatBase10, we can build Fmt, which formats in standard exponential notation:

// Fmt formats d, p into s in exponential notation. // The caller must pass nd set to the number of digits in d. // It returns the number of bytes written to s. func Fmt(s []byte, d uint64, p, nd int) int { // Put digits into s, leaving room for decimal point. formatBase10(s[1:nd+1], d) p += nd - 1 // Move first digit up and insert decimal point. s[0] = s[1] n := nd if n > 1 { s[1] = '.' n++ } // Add 2- or 3-digit exponent. s[n] = 'e' if p < 0 { s[n+1] = '-' p = -p } else { s[n+1] = '+' } if p < 100 { s[n+2] = i2a[p*2] s[n+3] = i2a[p*2+1] return n + 4 } s[n+2] = byte('0' + p/100) s[n+3] = i2a[(p%100)*2] s[n+4] = i2a[(p%100)*2+1] return n + 5 }

When calling Fmt with a FixedWidth result, we know the digit count nd already.

For a Short result, we can compute the digit count easily from the bit length:

// Digits returns the number of decimal digits in d.

func Digits(d uint64) int {

nd := log10Pow2(bits.Len64(d))

return nd + bool2[int](d >= uint64pow10[nd])

}Fixed-Width Performance

To evaluate fixed-width printing,

we need to decide which floating-point values to convert.

I generated 10,000 uint64s in the range and used them as

float64 bit patterns.

The limited range avoids negative numbers, infinities, and NaNs.

The benchmarks all use Go’s

ChaCha8-based generator

with a fixed seed for reproducibility.

To reduce timing overhead, the benchmark builds an array of 1000 copies of the value

and calls a function that converts every value in the array in sequence.

To reduce noise, the benchmark times that function call 25 times and uses the median timing.

We also have to decide how many digits to ask for:

longer sequences are more difficult.

Although I investigated a wider range, in this post I’ll show

two representative widths: 6 digits (C printf’s default) and 17 digits

(the minimum to guarantee accurate round trips, so widely used).

The implementations I timed are:

-

dblconv: Loitsch’s double-conversion library, using the

ToExponentialfunction. This library, used in Google Chrome, implements a handful of special cases for small binary exponents and falls back to a bignum-based printer for larger exponents. -

dmg1997: Gay’s

dtoa.c, archived in 1997. For our purposes, this represents Gay’s original C implementation described in his technical report from 1990 [12]. I confirmed that this 1997 snapshot runs at the same speed as (and has no significant code changes compared to) another copy dating back to May 1991 or earlier. -

dmg2017: Gay’s

dtoa.c, archived in 2017. In 2017, Gay published an updated version ofdtoa.cthat usesuint64math and a table of 96-bit powers of ten. It is significantly faster than the original version (see below). In November 2025, I confirmed that the latest version runs at the same speed as this one. -

libc:

The C standard library conversion using

sprintf("%.*e", prec-1). The conversion algorithm varies by C library. The macOS C library seems to wrap a pre-2017 version ofdtoa.c, while Linux’s glibc uses its own bignum-based code. In general the C library implementations have not kept pace with recent algorithms and are slower than any of the others. -

ryu: Adams’s Ryū library, using the

d2exp_bufferedfunction. It uses the Ryū Printf algorithm [3]. - uscale: The unrounded scaling approach, using the Go code in this post.

- uscalec: A C translation of the unrounded scaling Go code.

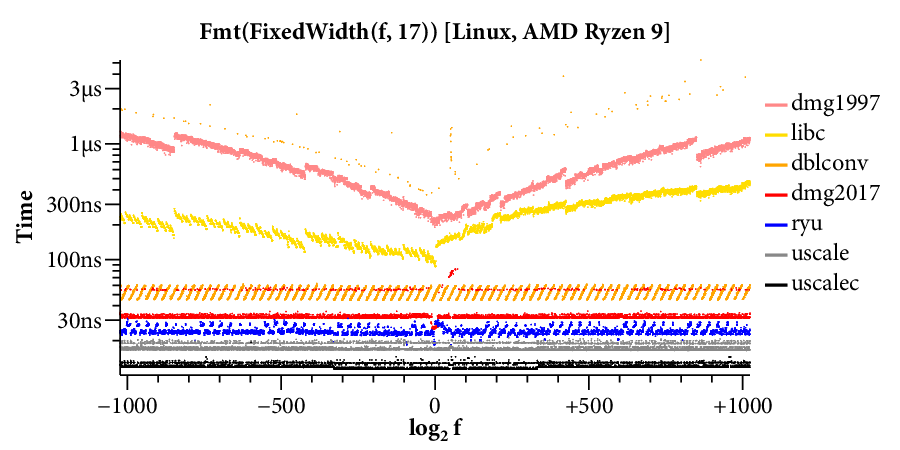

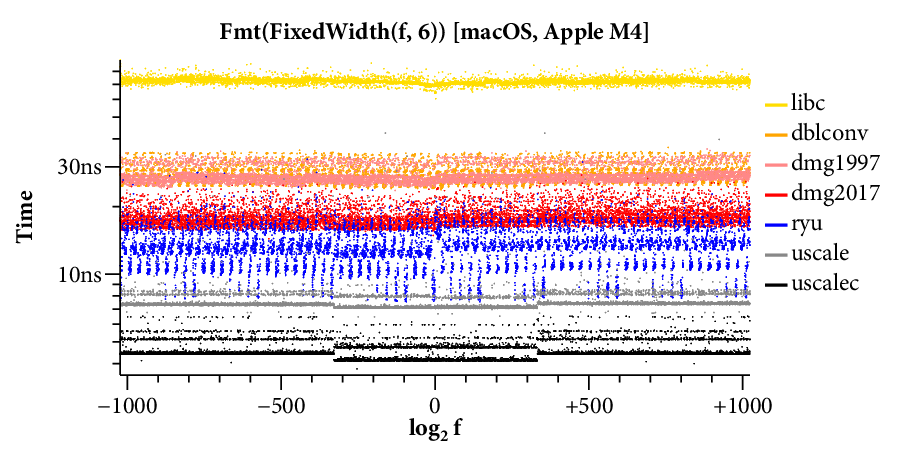

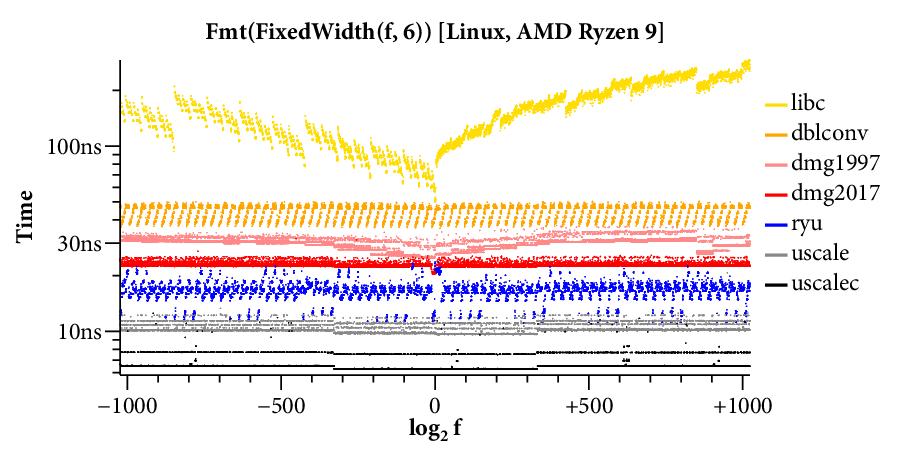

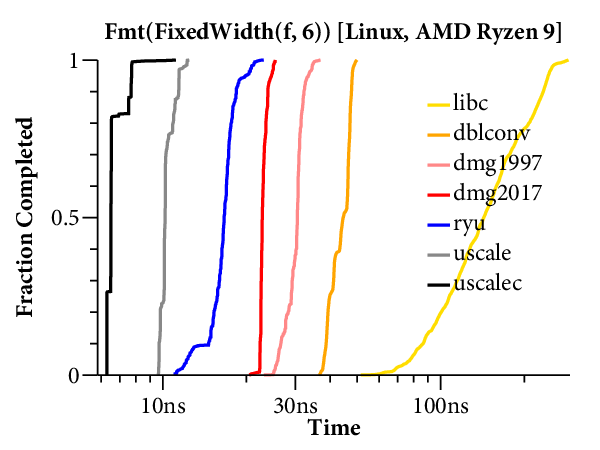

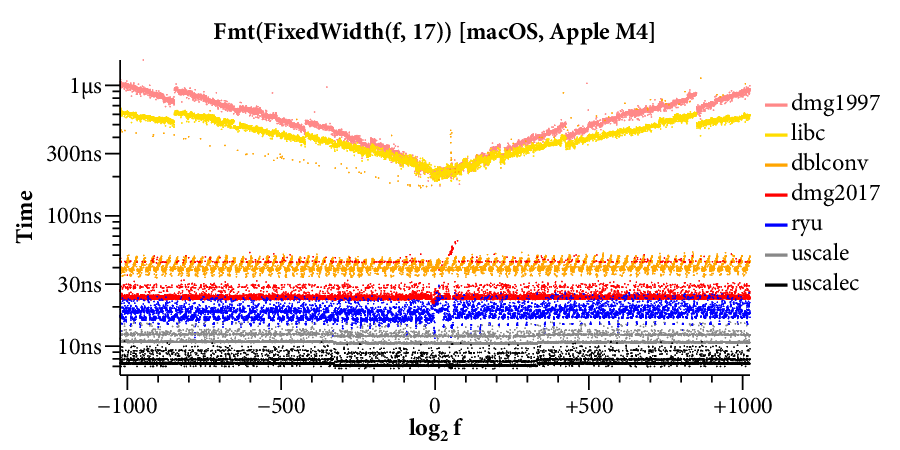

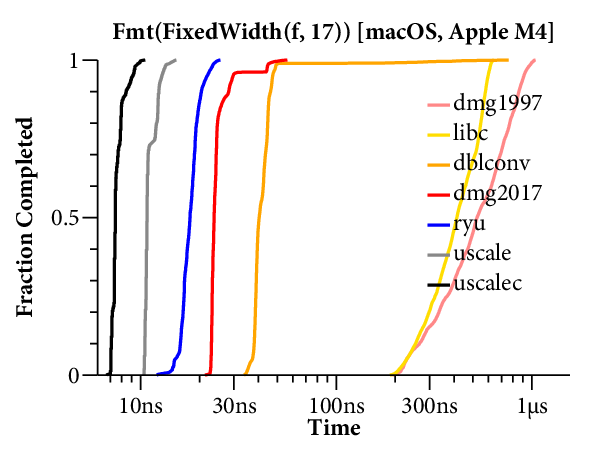

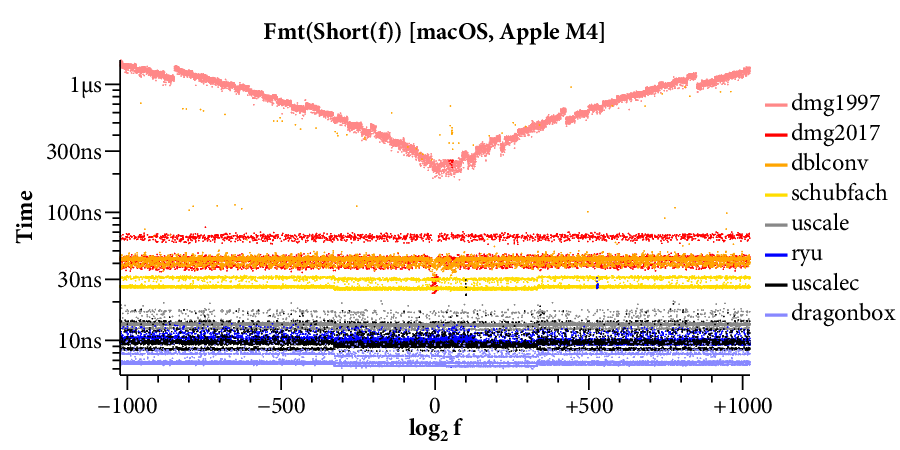

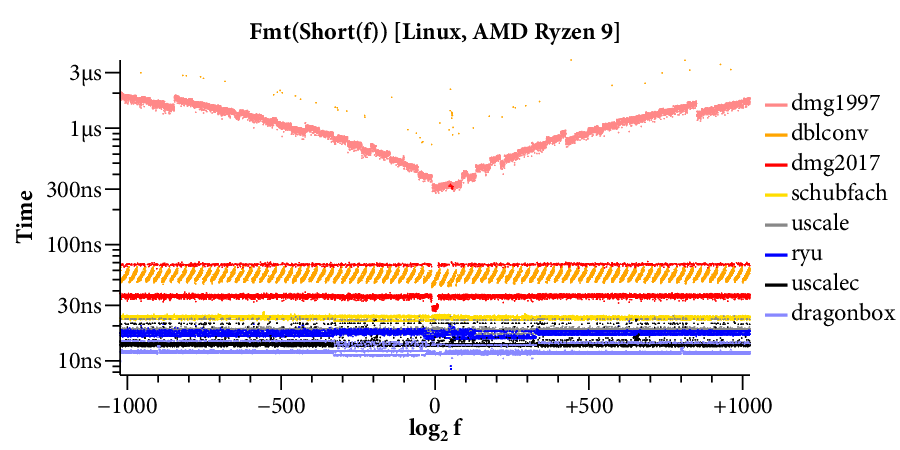

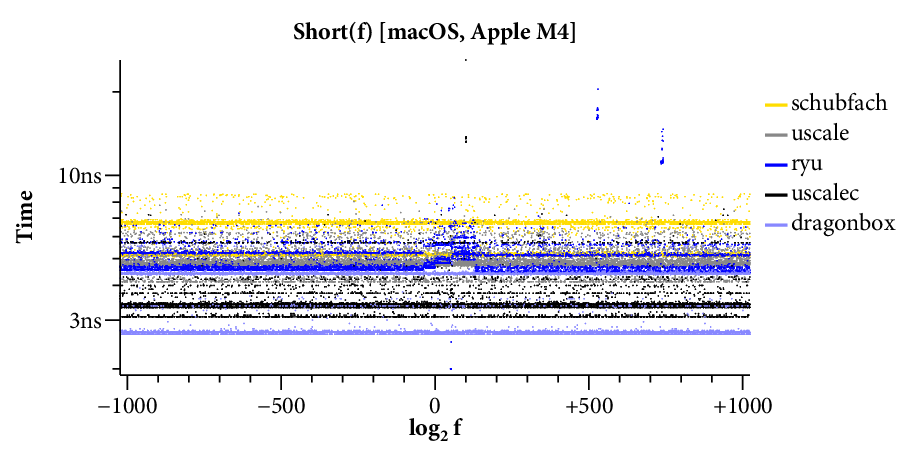

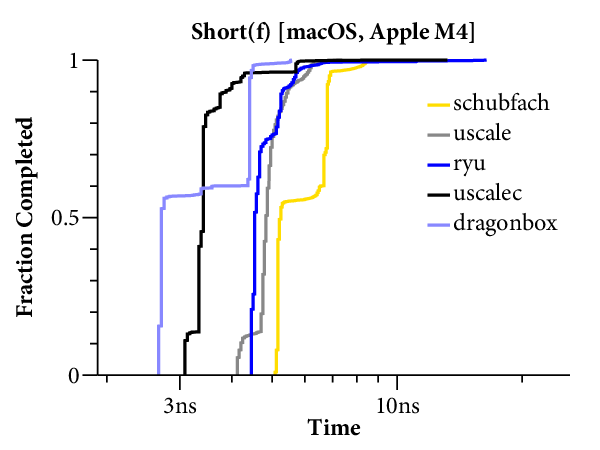

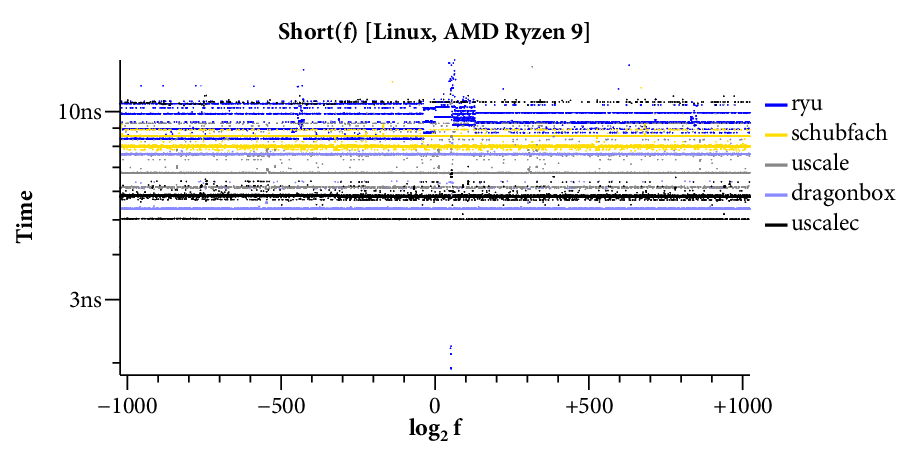

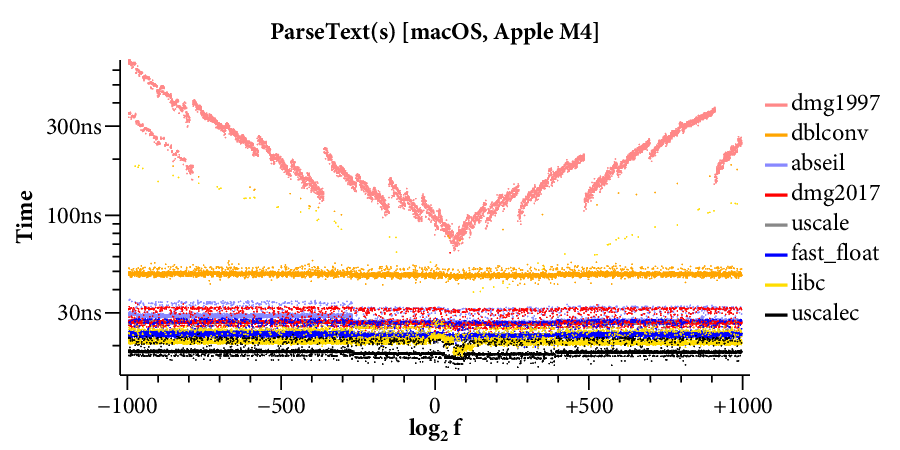

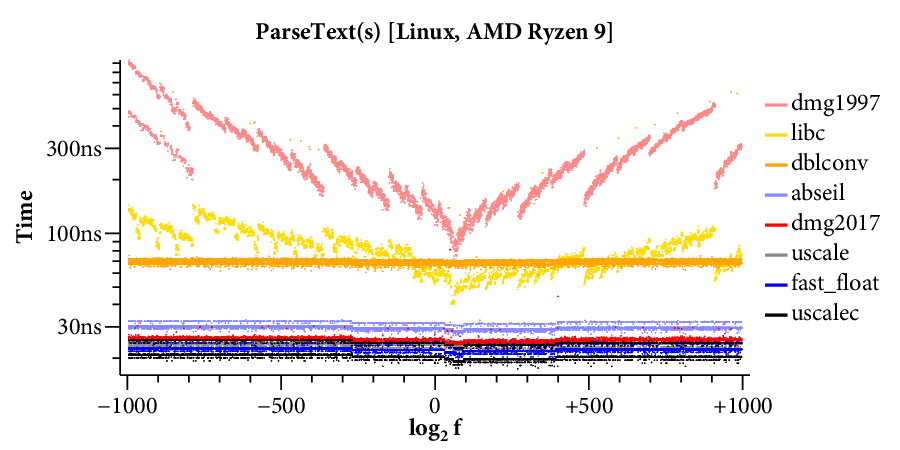

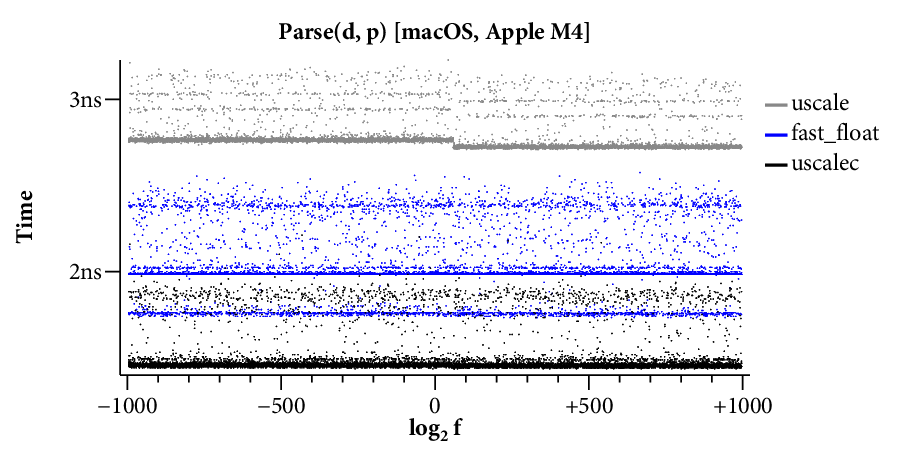

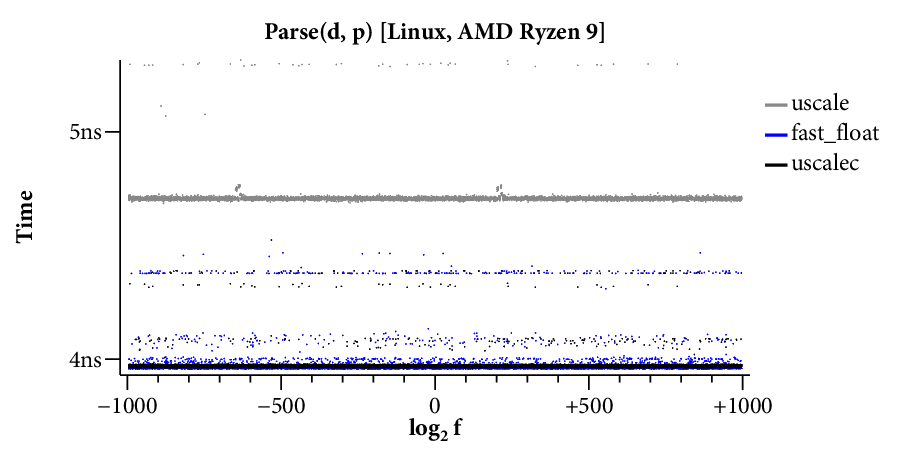

Here is a scatterplot showing the times required to format to 17 digits, running on the Linux system:

(Click on any of the graphs in this post for a larger view.)

The X axis is the log of the floating point input , and the Y axis is the time required for a single conversion of the given input. The scatterplot makes many things clear. For example, it is obvious that there are two kinds of implementations. Those that use bignums take longer for large exponents and have a “winged” scatterplot, while those that avoid bignums run at a mostly constant speed across the entire exponent range. The scatterplot also highlights many interesting data-dependent patterns in the timings, most of which I have not investigated. A friend remarked that you could probably spend a whole career analyzing the patterns in this one plot.

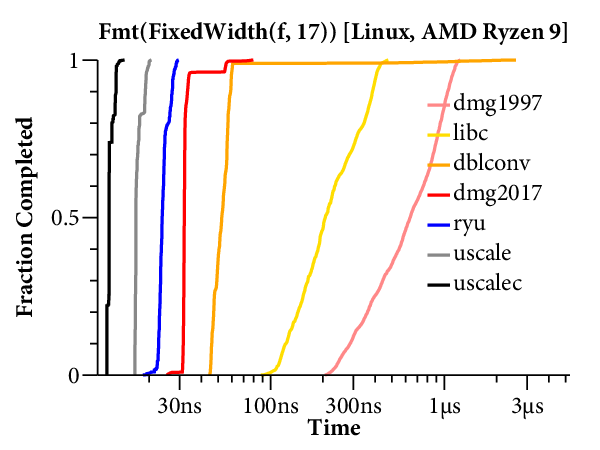

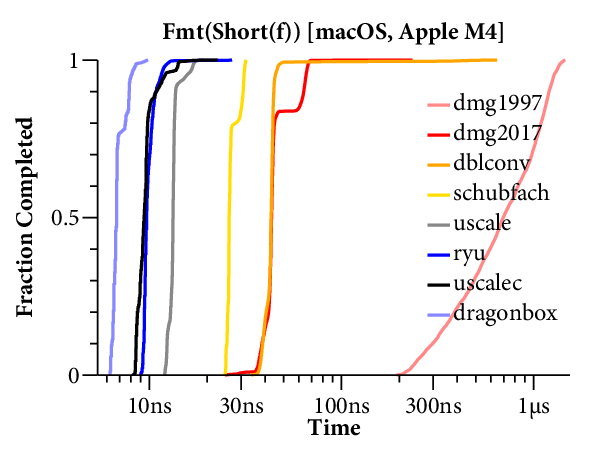

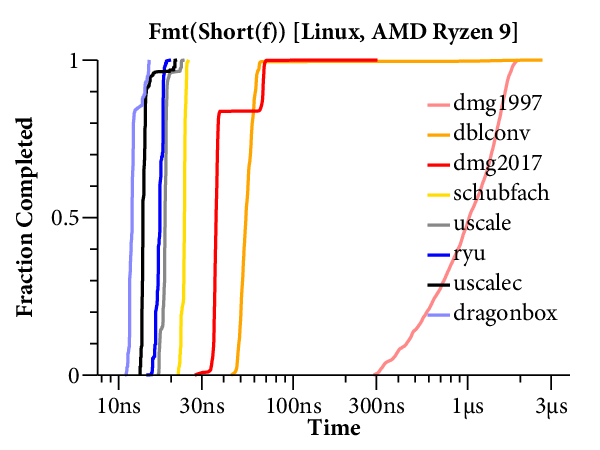

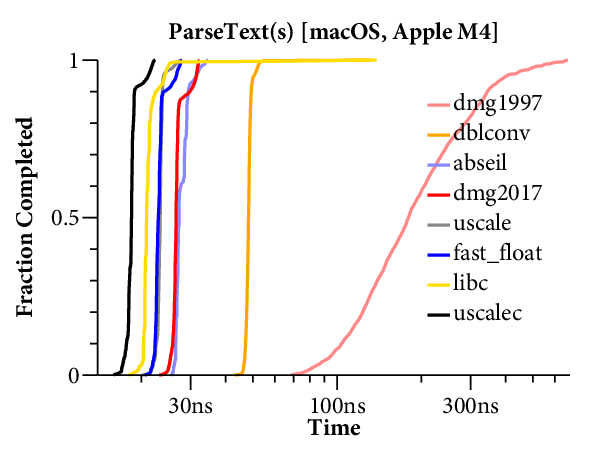

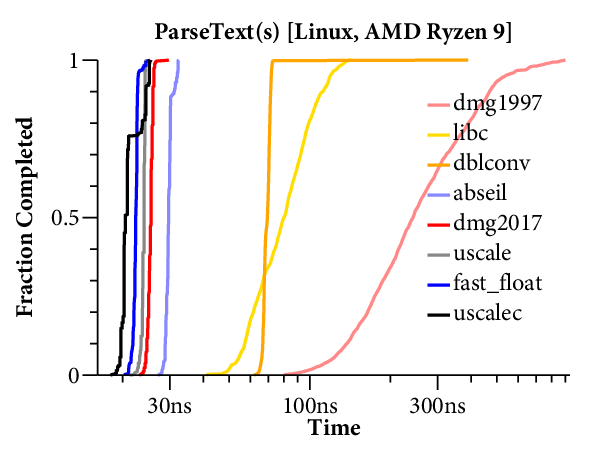

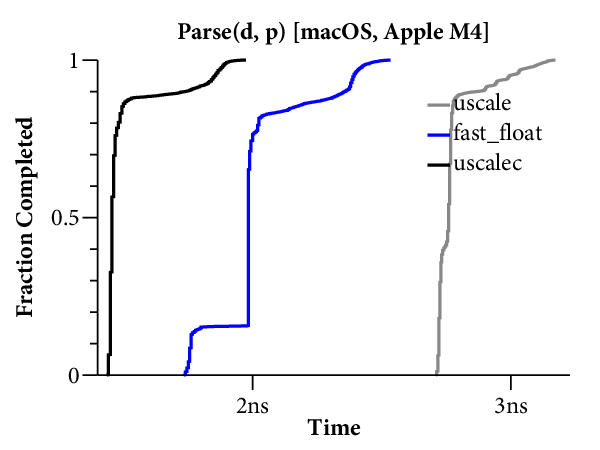

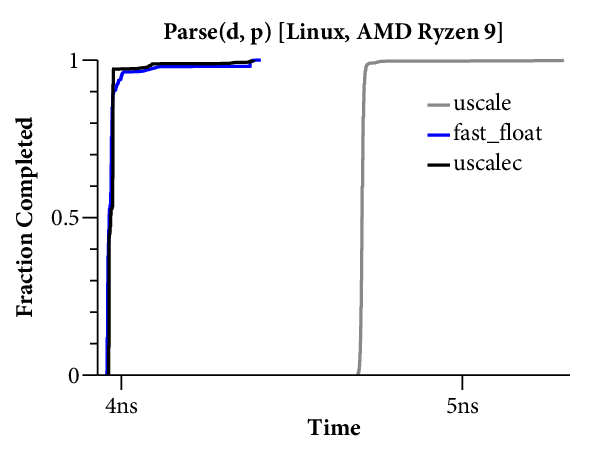

For our purposes, it would help to have a clearer comparison of the speed of the different algorithms. The right tool for that is a plot of the cumulative distribution function (CDF), which looks like this:

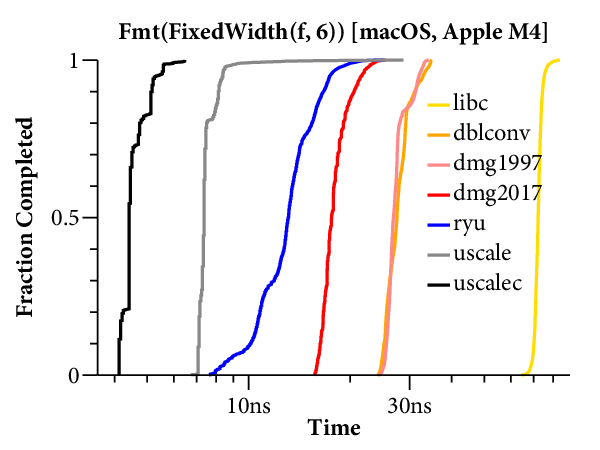

Now time is on the X axis (still log scale), and the Y axis plots what fraction of the inputs ran in that time or less. For example, we can see that dblconv’s fast path applies to most inputs, but its slow path is much slower than Linux glibc or even Gay’s original C library.

The CDF only plots the middle 99.9% of timings (dropping the 0.05% fastest and slowest), to avoid tails caused by measurement noise. In general, measurements are noisier on the Mac because ARM64 timers only provide ~20ns precision, compared to the x86’s sub-nanosecond precision.

Here are the scatterplots and CDFs for 6-digit output on the two systems: