What NPM Should Do Today To Stop A New Colors Attack Tomorrow

Russ Cox

January 10, 2022

research.swtch.com/npm-colors

Posted on Monday, January 10, 2022.

January 10, 2022

research.swtch.com/npm-colors

Over the weekend, a developer named Marak Squires intentionally sabotaged his popular NPM package colors and his less popular package faker. As I write this, NPM claims 18,971 direct dependents for colors and 2,751 for faker. Open Source Insights counts at least 42,000 more indirect dependents for colors. Many popular NPM packages depend on these packages.

A misfeature in NPM’s design means that as soon as the sabotaged version of colors was published, fresh installs of command-line tools depending on colors immediately started using it, with no testing that it was in any way compatible with each tool. (Spoiler alert: it wasn’t!)

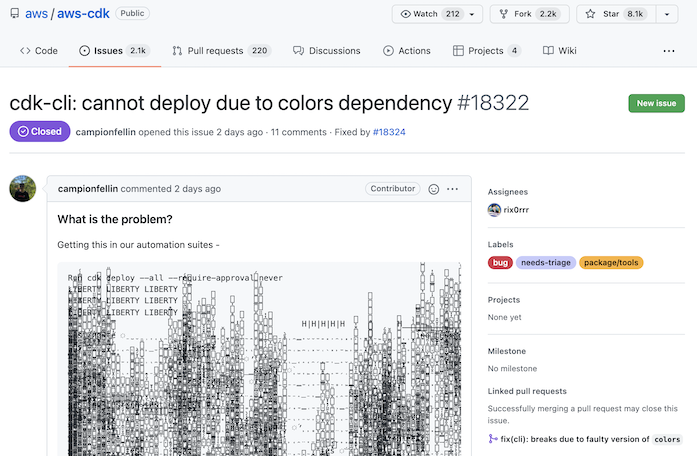

The specific misfeature is that when you use NPM to install a package, including a command-line tool, NPM selects the dependency versions according to the requirements listed in package.json as well as the state of the world at that moment, preferring the newest possible allowed version of every dependency. This means that the moment Marak updated colors, installs of aws-cdk and the other tools started breaking, and the bug reports started rolling in, like this one:

And also these in apostrophe, cdk8s, compodoc, foreversd, hexo, highcharts, jest, netlify, oclif, and more.

NPM users may be upset at Marak today, but at least the change didn’t do anything worse than print garbage to the terminal. It could have been worse. A lot worse. Even ignoring this kind of intentional breakage, innocent bugs happen all the time too. Essentially every open source software license points out that the code is made available with no warranty at all. Modern package managers need to be designed to expect and mitigate this risk.

Anyone running modern production systems knows about testing followed by gradual or staged rollouts, in which changes to a running system are deployed gradually over a long period of time, to reduce the possibility of accidentally taking down everything at once. For example, the last time I needed to make a change to Google’s core DNS zone files, the change was tested against many many regression tests and then deployed to each of Google’s four name servers, one at a time, over a period of 24 hours. Regression testing checks that the change does not appear to affect answers it shouldn’t have, and then the gradual rollout gives plenty of time for both automated systems and reliability engineers to notice unexpected problems and stop the rollout.

NPM’s design choice is the exact opposite. The latest version of colors was promoted to use in all its dependents before any of them had a chance to test it and without any kind of gradual rollout. Users can disable this behavior today, by pinning the exact versions of all their dependencies. For example here is the fix to aws-cdk. That’s not a good answer, but at least it’s possible.

The right path forward for NPM and package managers like it is to stop preferring the latest possible version of all dependencies when installing a new package. Instead, they should prefer to use the dependency versions that the package was actually tested with, or versions as close as possible to those. I call that a high-fidelity build. In contrast, the people who installed aws-cdk and other packages over the weekend got low-fidelity builds: NPM inserted a new version of colors that the developers of these other packages had never tested against. Users got to test that brand new configuration themselves over the weekend, and the test failed.

High-fidelity builds solve both the testing problem and the gradual rollout problem. A new version of colors wouldn’t get picked up by an aws-cdk install until the aws-cdk authors had gotten a chance to test it and push a new version configuration in a new version of aws-cdk. At that point, all new aws-cdk installs would get the new colors, but all the other tools would still be unaffected, until they too tested and officially adopted the new version of colors.

There are many ways to produce high-fidelity builds. In Go, a package declares the minimum required version of each dependency, and that’s what the build uses, unless some other constraint in the same build graph requests a newer one. And then, it only uses that specific newer one, not the one that just appeared over the weekend and is entirely untested by anyone. For more about this approach, see “The Principles of Versioning in Go.”

Package managers don’t have to adopt Go’s approach exactly. It would be enough, for example, to record the versions that the aws-cdk developers used for their testing and then reuse those versions during the install. In fact, NPM can already record those versions, in a lock file. But npm install of a new package does not use the information in that package’s lock file to decide the versions of dependencies: lock files are not transitive.

NPM also has an npm shrinkwrap command, as well as an npm ci command, both of which appear to fix this problem in certain, limited circumstances. Most of the authors and users of commands affected by the colors sabotage should be looking carefully at those today. Kudos to NPM for providing those, but they shouldn’t be off to the side. The next step is for NPM to arrange for that kind of protection to happen by default. And then the same protection is needed when installing a new library package as a dependency, not just when installing a command. All this will require more work.

Other language package managers should take note too. Marak has done all of us a huge favor by highlighting the problems most package managers create with their policy of automatic adoption of new dependencies without the opportunity for gradual rollout or any kind of testing whatsoever. Fixing those problems is long overdue. Next time will be worse.